"Atlantica Trust" r.-t.

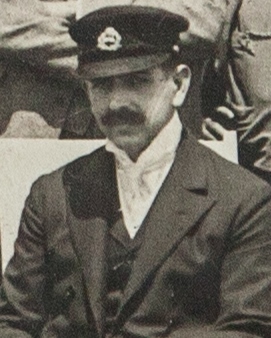

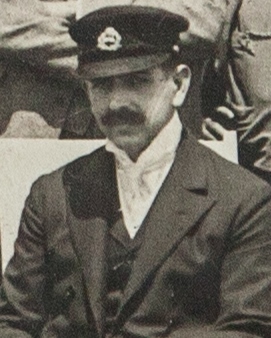

The history of Atlantica Ltd. before and during the First World War is already a well-established story, well embedded in the history of Hungarian shipping. Jenő Polnay was born on 20 August 1873 in Tiszasüly into a Jewish timber merchant family. As a young man he studied law in Debrecen, then economics in the Czech Republic. In his early twenties he was already manager of the Transylvanian Timber Company, and in 1900 he moved to London, where he became manager of the Groedel brothers' steamship company. It was at this time that he learnt the business of shipping, while at the same time building up a network of contacts with those interested in economic relations between Britain and Austria-Hungary. The focal point for these was the Anglo-Austrian Bank, which, together with other British partners, assured Polnay that if the Hungarian government supported a newly formed free shipping company, they would provide the necessary capital.

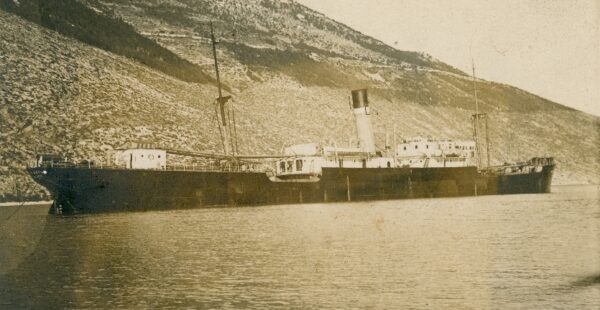

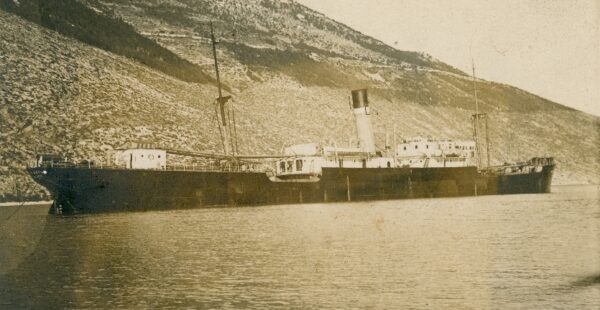

Polnay successfully negotiated with the then Minister of Commerce, Count Béla Serényi, because the government increased the shipbuilding and freight subsidies in Article VI of Law 1907 compared to those in Article XXII of Law 1893. With this in mind, the Atlantica Shipping Company was set up in 1906 and had its cargo steamships built in the best British shipyards, which, according to the available literature, proved very profitable, and the company prospered until the outbreak of the Great War in 1914.

For his merits in the field of merchant navy, he received Hungarian nobility with the first name of Tiszasüly from József Ferencz in 1911. He later took on a political role, becoming Minister of Public Food in the Friedrich government from 7 to 15 August 1919.

- On 28 July, the outbreak of war put the Atlantic in an awkward position, with its ships in many different parts of the world, all of which were due to return home or to a neutral port as soon as possible.

- The SS Szterényi left Newport for Fiume on 21 July, arriving on 4 August.

- The SS Hungary left Penarth on 24 July and arrived in Fiume on 7 August.

- The SS Polnay sailed from the Al-Duna to London in early July, where the British seized it before the outbreak of war and took possession of it, during which time it sank. As the seizure of the ship was illegal, after the war the British paid compensation of £50,000 to the Atlantian.

- The SS Kossuth Ferencz arrived in Fiume on 26 July.

- The SS Morawitz arrived in Amsterdam on 8 July, from where it departed for Galvestone (USA).

- The SS Count Serényi Béla left Braila for Rotterdam on 28 July and was able to reach a neutral port in Cartagena (Spain).

- The SS Budapest arrived from Cardiff to Buenos Aires on 20 April, from where it sailed to Norfolk (USA) in June and July.

- The SS Fiume departed Port Talbot for Fiume on 21 July and arrived in Pola in the first days of August.

- The SS Count Khuen Héderváry left Rotterdam for Fiume on 14 July, arriving on 7 August.

- The SS Atlantica departed Odessa for Rotterdam on 25 July, but managed to pull into Ferrol (Spain) en route.

The two steamers that reached the US were sold by Atlantica to local merchants during 1916, before the US entered the war, for 2 100 000 $. The returning steamers were to be used under the Free Navigation Acts for war purposes coordinated by the War Department, primarily for troop and transport movements.

The documents of the general assembly of 1917 indicate that the company envisaged the construction of Danube cruise ships (6,000-7,000 tons), and accordingly the plan to convert the bridges at Baja, Novi Sad and Zombor into openable ones; and the establishment of its own shipyard, for which the Háros and Hunyadi islands near Budafok were purchased for the price of the ships sold to the USA, and the forests on which they were immediately cleared.

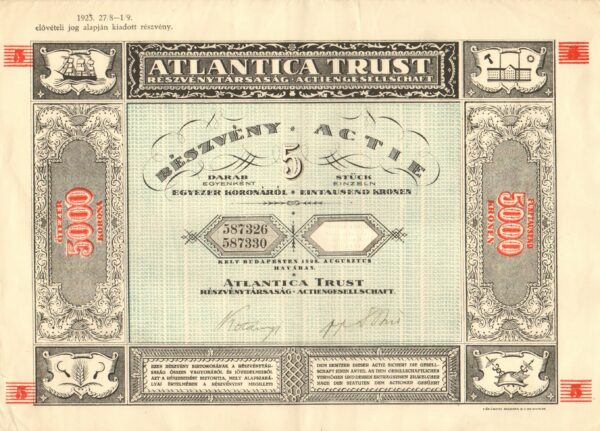

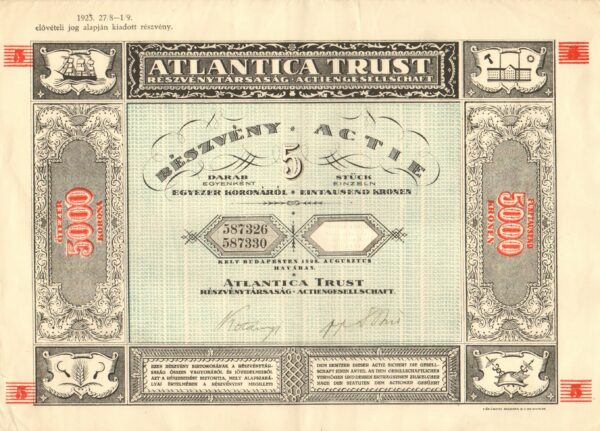

The fact that Polnay is credited with the invention of the Danube cruise is proven not only by the documents of the General Assembly, but also by the fact that the highly qualified naval captain Ernő Roediger of the Maritime Authority also examined the issue on a professional basis. According to Roediger's calculations, a 3 600-tonne steamer to be built in Budapest would have a draught of 2.2 metres when empty, a 7 000-tonne steamer 3.25 metres; the Danube would have enough water for 180 days for the former and 130 days for the latter. Only the bridges at Baja, Zombor and Novi Sad would have had to be raised enough to allow ships to pass under them. To carry out this ambitious plan, the company was restructured and in 1921 the Atlantica Trust was formed.

If all this had happened in peacetime, in a boom, we would certainly still be talking about Atlantica with the biggest multinationals, because Polnay was able to unite the most diverse participants in economic and social life, from the bourgeois intelligentsia to the big businessmen and the aristocracy. In reality, however, after the creation of the Atlantica Trust, the company was largely hit by a negative economic shock, and by the end of the 1920s it was essentially insolvent.

The essence of the 1918 reorganisation was that Atlantica Shipping Ltd. became the headquarters and umbrella organisation of a large group of companies, which participated as a legal entity in the establishment of new subsidiaries. Although the company name was changed to Atlantica Trust in 1921, this trust was not the form of organisation prohibited in this country, for example, by Article IX of Law No. 1916, i.e. when a cartel agreement is created within an industry. The Atlantica Trust envisaged cooperation between industries, so the articles of association provided for participation in shipping, transport, agriculture, textiles, chemicals, the colonial trade, porcelain, glass, rubber, surgical instruments, wine, beer and spirits, timber and firewood, machinery and parts. It can be said that Atlantica has included in its articles of association a significant number of the professions that can be practised.

Under the ceasefire that ended the war, Atlantica's ships were requisitioned by the Entente. Only fragmentary sources have survived concerning the company's inland fleet on the Danube. In the light of these, the fleet had a very broad portfolio: elevators, dredgers, dredgers, barges, barges, screw steamers, paddle steamers. It is interesting to note that, along with the tugs Turkish and Storm, the poet Attila József served as a petty officer on board in 1920, when he was a young man.

The Atlantica report for the 1919 business year was very positive, except for the possible fate of the ships. Polnay systematically bought his way into a wide variety of businesses. Such investments included the Újpest dredging factory, the Érd steam-brickworks, and the Piszke quarry. With the help of these businesses, the Atlantica shipyard, the clerks' apartments and the canteen were built on the Háros- and Hunyadi Islands.

The ships acquired and the companies affiliated were all intended to make it easier for Polnay to build on the island of the City. As part of this, he connected the Háros and Hunyadi Islands to each other and to the mainland (Budafok) on the right bank of the Danube. And the raw materials he did not need, he sold on the market - 75 000 m3 was. On the now peninsula, Polnay also set up a public storage company and equipped the shipyard by purchasing the Schlick-Nicholson Mosquito Island shipyard's equipment. The trees on the island were felled and sold to the Szikra match factory in Budafok.

In addition to these, Atlantica Trust founded Terramare Transport Rt, Hydroflora Reed, Seed and Herb Factory Rt, Sideron Iron Trading Company, took over Duna-Rajna Trading Rt, Fővárosi Nyomda Rt and Continental Film Factory in Sashalm where raw film was produced for the film industry; and leased the Fotocines Italiana laboratory in Rome and the Astoria laboratory in Budapest. They also engaged in a commodity business, exporting domestic products and importing goods not available at home. Thus they became the sole Hungarian representative of a large Canadian asbestos mine. They leased the Herkules bitter water springs in Budafok, which had 17 wells in a fully equipped plant, and whose products they intended to export to America, Anglia, Italy and Africa. They organised coal imports through their sea-going ships. They attempted to finance a rural mill to export flour to Vienna, the Czech Republic and Germany. They exported walnuts to North America, but also other commodities such as salami, peppers, tinned peppers and sorghum. From Romania, they imported petrol and petroleum, and even transported live cattle by rail to Italy, where they were 'sold at a good price'.

In addition to this, Atlantica also began to engage in banking, such as stockbroking, bill discounting and foreign exchange, but Polnay's biggest deal was the founding and construction of the Lanaria postal factory on the island of Harbour, which drove the first nail into the coffin of Atlantica Trust with an investment of £300,000.

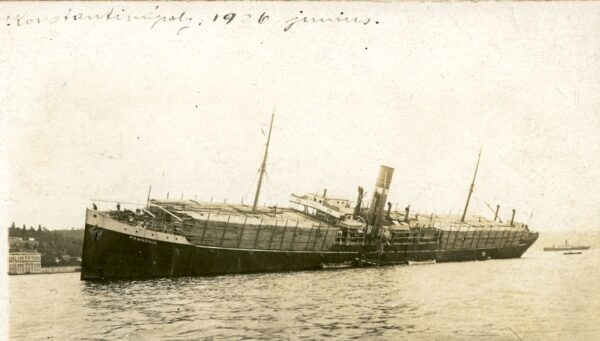

After the armistice of 3 November 1918, the former Atlantica ships were placed under the control of the Entente countries. After the Trianon peace treaty was signed in 1921, the Hungarian Government expropriated the Atlantica ships under the terms of Article XVI of Law 1922, promising compensation, and handed them over to the Reparation Commission, which gave the SS Atlantica to Yugoslavia and the other ships to Italy. Atlantica thus lost overnight its fleet, which had been built up with great care since 1907 and was the basis of all its financial development.

Polnay, aware of the serious consequences of the loss of the fleet, immediately entered into negotiations with the Italian government and succeeded in reaching an agreement. Under the terms of the agreement, in view of the interests of Fiuma, Atlantica Trust and the Italian Government set up a joint venture company, Fiumana Soceitá Anonima di Navigazione (Fiumana Shipping Company), with a share capital of ITL 1 000 000, in which the parties held 50-50% shares, the Italians providing the former Atlantica fleet (47 000 tonnes deadweight) and Atlantica managing the ships. In the new company, however, the names of the ships had to be Italianised. Thus Fiume became Fiumana, Count Khuen Héderváry became Atlantica, Count Serényi Béla became Danubio, Kossuth Ferencz became Alberto Fassini, Hungary became Ungheria and Szterényi became Budapest.

The ships generated some income in the early years, but the fleet was steadily depreciating as competitors operated much more modern steamers. Finally, the Great Depression gave Fiumana a reprieve. In the meantime, by the early 1930s, Atlantica Trust had become insolvent, because the Hungarian state refused to compensate the company for the expropriation of the property, nor to do anything about it, despite Polnay's constant requests to the ministries...

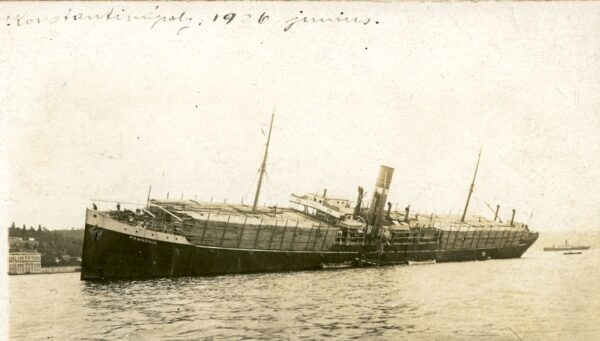

In another great feat, however, Polnay was able to found another entirely Hungarian shipping company in 1923. Elek Bíró writes about this. As Polnay had no money left, and currency difficulties made it impossible to resolve the matter, he proposed to the Harrimans that they should form a shipping company, the American Ship & Commerce Navigation Corporation. The shares in the company would be owned by Harriman and he would take over the fleet from Harriman, but he would not pay for it, i.e. it would be a simple change of flag. Harriman will transfer the ships to Oceana Navigation Ltd. for management. Half of Oceana's shares are owned by Harriman, the other half by Atlantica, the profits are used to make purchase payments to Harriman and when the agreed purchase price is settled by these payments the ships are transferred to Oceana. So Harriman eventually sells the ships, receives the purchase price and still owns half of the value of the ships and is part of a 50% earning deal. However, Atlantica, after paying the purchase price, owns half of the fleet without investing a penny. Meanwhile, it manages the ships and receives a commission of 3% for the transport".

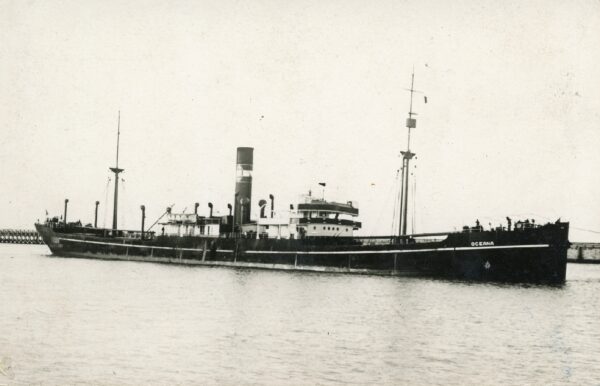

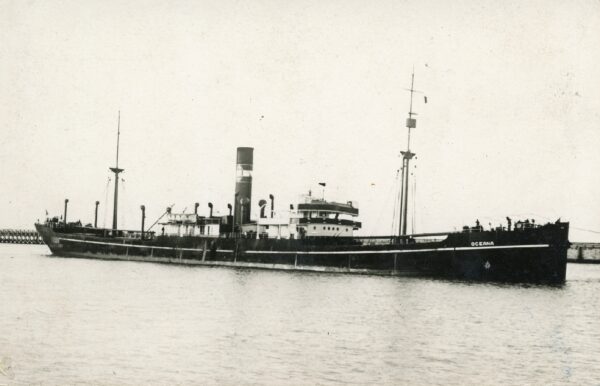

The Oceana Shipping Company thus established started with great hopes, but the shipping depression of the second half of the decade left its mark on the company's operations, and with little revenue, Atlantica's financial deficit grew steadily due to claims on the government, and it was eventually unable to repay Harriman. The fleet consisted of the following ships: Oceana (8 100 tons deadweight), Pannonia (7 300 tons), Debrecen (6 500 tons), Balaton (6 100 tons), Alföld (5 100 tons), Háros (3 500 tons) and the original Atlantica fleet Morawitz. The ships were crewed by old Atlantians, so Hungarian sailors and engineers served under the Hungarian flag.

The Hungarian Statistical Yearbooks publish data on the operation of the Hungarian merchant marine between 1923 and 1939, but only the turnover of Oceana Shipping Ltd. is recorded for the period 1923-1929. In the light of this, it can be said that the company operated 7 ships (17 790 NRT capacity) between 1923 and 1926. Each year it made 40 to 42 voyages with its ships. It carried 236 800 tonnes in 1923, 220 000 tonnes in 1924, 235 600 tonnes in 1925 and 214 666 tonnes in 1926. Between 1928 and 1929, however, it had only one ship with a capacity of 2 595 NRT, carrying 27 711 tonnes of goods in 1928 and 55 193 tonnes in 1929, with 16 voyages a year. Oceana finally went into liquidation in 1929, before the outbreak of the economic crisis, which ended in 1943 when neither the Atlantica Trust nor the Harriman company, which had been hit hard by the 1929 crisis, were able to recover their claims.

To summarize what has been described so far, by the early 1930s the Atlantica group was essentially bankrupt, having lost all its profitable business, and the majority owner, the former Anglo-Austrian Bank, had sold what it could. There was only one step left to liquidate Atlantica Trust, the recovery of claims against the Hungarian state and the payment of the shareholders, but this was eventually lost in the labyrinths of Hungarian bureaucracy and can be assumed never to have been resolved. Jenő Polnay Tiszasülyi, the founder of the company, had to leave the management in disgrace. When he read in the Budapest Gazette of 25 April 1944 (Tuesday) the Ministerial Decree 1540/1944 on the termination of the employment and occupation of Jews in the intellectual professions, which came into force on that day, he informed the Company Court, as a law-abiding citizen, that he understood that this meant the end of his membership of the board of directors of Atlata.

Sources

Archives of the Capital of Budapest.

VII-2-e: Company court documents.

02042-1915 Atlantica Shipping Company (1907-1944).

11163-1920. Duna-Rajna Trading Company (1920-1924).

11959-1920. Textile and Carpet Factory Ltd (1920-1944).

16315-1921. Hydroflora Hungarian Reed, Cane and Herb Company (1921-1941).

16325-1921. Hungarian American Shipping Company (1921-1929).

16511-1922. Oceana Shipping Company (1922-1944).

17374-1922. Sideron Iron, Metal, Technical and Chemical Products Ltd (1922-1933).

18275-1922. Terra Mare Transport Ltd (1922-1933).

30226-1929. Zoltán Czukker Herkules Hungarian Bitter Water Spring Company (1929).

Hungarian National Archives. National Archives. Z. 1070. ATLANTICA Shipping Company (1887-1929).

Državni Arhiv u Rijeci - Rijeka State Archives. Maritime Authority records (DAR-46).

Hungarian Museum of Technology and Transport. Manuscript archive.

Népszava 11 April 1980, issue 6.

Róbert Bagdi - Norbert Hlbocsányi (2020). In György Kövér - Ágnes Pogány - Boglárka Weisz (eds.): Hálózat és Hierarchia. Hungarian Economic History Yearbook. Budapest. 465-486.

Gatshcer-Riedl, Gregor (2022): Steamer under the double eagle. Merchant ships and shipping companies in the Habsburg Monarchy. Berndorf.

Herczeg, Renáta - Prakfalvi, Endre (2016):The construction works of the Atlantica Shipping Company in the end days of the monarchy on Háros Island. Monument Protection 60. 3-4. nos. 207-230.

János Illésy - Béla Pettkó (eds.): Royal Books. Budapest. https://archives.hungaricana.hu/hu/libriregii/

Hungarian Compass: https://adt.arcanum.com/hu/collection/MagyarCompass/

TEXT: Hungarian Biographical Dictionary. https://mek.oszk.hu/00300/00355/html/

MSÉ (1919-1946): Hungarian Statistical Yearbooks. Published by the Royal Hungarian Central Statistical Office. https://adt.arcanum.com/hu/collection/MagyarStatisztikaiEvkonyv/

Márton Pelles (2019): History of Atlantica Shipping Company (1907-1918). XI. 1. 35-48.

Márton Pelles (2023):History of the Atlantica Trust (1906-1944).

789-814.

Márton Pelles (2024):The history of the Hungarian merchant navy between 1921-1945. Monograph, manuscript.

Márton Pelles - Gábor Zsigmond (2021):History of the Hungarian merchant navy of Rijeka 1868-1921.

János Schláth (2017): misplaced heritage. Szemelvények a magyar maritime history. From the history of Hungarian maritime history. The author's private publication.

Date of foundation: 1906

Date of cessation: 1944

Founders: Jenő Polnay, Anglo-Hungarian Bank, Barons Groedel

Securities issued:

| "Atlantica Trust" r.-t. |

Decisive leaders:

1906-1944 | Jenő Polnay from Tiszasüly |

Main activity: maritime shipping, shipbuilding

Author: by Dr. Márton Pelles

Date of foundation: 1906

Founders: Jenő Polnay, Anglo-Hungarian Bank, Barons Groedel

Decisive leaders:

1906-1944 | Jenő Polnay from Tiszasüly |

Main activity: maritime shipping, shipbuilding

Main products are not set

Seats are not configured

Locations are not set

Main milestones are not set

Author: by Dr. Márton Pelles

"Atlantica Trust" r.-t.

The history of Atlantica Ltd. before and during the First World War is already a well-established story, well embedded in the history of Hungarian shipping. Jenő Polnay was born on 20 August 1873 in Tiszasüly into a Jewish timber merchant family. As a young man he studied law in Debrecen, then economics in the Czech Republic. In his early twenties he was already manager of the Transylvanian Timber Company, and in 1900 he moved to London, where he became manager of the Groedel brothers' steamship company. It was at this time that he learnt the business of shipping, while at the same time building up a network of contacts with those interested in economic relations between Britain and Austria-Hungary. The focal point for these was the Anglo-Austrian Bank, which, together with other British partners, assured Polnay that if the Hungarian government supported a newly formed free shipping company, they would provide the necessary capital.

Polnay successfully negotiated with the then Minister of Commerce, Count Béla Serényi, because the government increased the shipbuilding and freight subsidies in Article VI of Law 1907 compared to those in Article XXII of Law 1893. With this in mind, the Atlantica Shipping Company was set up in 1906 and had its cargo steamships built in the best British shipyards, which, according to the available literature, proved very profitable, and the company prospered until the outbreak of the Great War in 1914.

For his merits in the field of merchant navy, he received Hungarian nobility with the first name of Tiszasüly from József Ferencz in 1911. He later took on a political role, becoming Minister of Public Food in the Friedrich government from 7 to 15 August 1919.

- On 28 July, the outbreak of war put the Atlantic in an awkward position, with its ships in many different parts of the world, all of which were due to return home or to a neutral port as soon as possible.

- The SS Szterényi left Newport for Fiume on 21 July, arriving on 4 August.

- The SS Hungary left Penarth on 24 July and arrived in Fiume on 7 August.

- The SS Polnay sailed from the Al-Duna to London in early July, where the British seized it before the outbreak of war and took possession of it, during which time it sank. As the seizure of the ship was illegal, after the war the British paid compensation of £50,000 to the Atlantian.

- The SS Kossuth Ferencz arrived in Fiume on 26 July.

- The SS Morawitz arrived in Amsterdam on 8 July, from where it departed for Galvestone (USA).

- The SS Count Serényi Béla left Braila for Rotterdam on 28 July and was able to reach a neutral port in Cartagena (Spain).

- The SS Budapest arrived from Cardiff to Buenos Aires on 20 April, from where it sailed to Norfolk (USA) in June and July.

- The SS Fiume departed Port Talbot for Fiume on 21 July and arrived in Pola in the first days of August.

- The SS Count Khuen Héderváry left Rotterdam for Fiume on 14 July, arriving on 7 August.

- The SS Atlantica departed Odessa for Rotterdam on 25 July, but managed to pull into Ferrol (Spain) en route.

The two steamers that reached the US were sold by Atlantica to local merchants during 1916, before the US entered the war, for 2 100 000 $. The returning steamers were to be used under the Free Navigation Acts for war purposes coordinated by the War Department, primarily for troop and transport movements.

The documents of the general assembly of 1917 indicate that the company envisaged the construction of Danube cruise ships (6,000-7,000 tons), and accordingly the plan to convert the bridges at Baja, Novi Sad and Zombor into openable ones; and the establishment of its own shipyard, for which the Háros and Hunyadi islands near Budafok were purchased for the price of the ships sold to the USA, and the forests on which they were immediately cleared.

The fact that Polnay is credited with the invention of the Danube cruise is proven not only by the documents of the General Assembly, but also by the fact that the highly qualified naval captain Ernő Roediger of the Maritime Authority also examined the issue on a professional basis. According to Roediger's calculations, a 3 600-tonne steamer to be built in Budapest would have a draught of 2.2 metres when empty, a 7 000-tonne steamer 3.25 metres; the Danube would have enough water for 180 days for the former and 130 days for the latter. Only the bridges at Baja, Zombor and Novi Sad would have had to be raised enough to allow ships to pass under them. To carry out this ambitious plan, the company was restructured and in 1921 the Atlantica Trust was formed.

If all this had happened in peacetime, in a boom, we would certainly still be talking about Atlantica with the biggest multinationals, because Polnay was able to unite the most diverse participants in economic and social life, from the bourgeois intelligentsia to the big businessmen and the aristocracy. In reality, however, after the creation of the Atlantica Trust, the company was largely hit by a negative economic shock, and by the end of the 1920s it was essentially insolvent.

The essence of the 1918 reorganisation was that Atlantica Shipping Ltd. became the headquarters and umbrella organisation of a large group of companies, which participated as a legal entity in the establishment of new subsidiaries. Although the company name was changed to Atlantica Trust in 1921, this trust was not the form of organisation prohibited in this country, for example, by Article IX of Law No. 1916, i.e. when a cartel agreement is created within an industry. The Atlantica Trust envisaged cooperation between industries, so the articles of association provided for participation in shipping, transport, agriculture, textiles, chemicals, the colonial trade, porcelain, glass, rubber, surgical instruments, wine, beer and spirits, timber and firewood, machinery and parts. It can be said that Atlantica has included in its articles of association a significant number of the professions that can be practised.

Under the ceasefire that ended the war, Atlantica's ships were requisitioned by the Entente. Only fragmentary sources have survived concerning the company's inland fleet on the Danube. In the light of these, the fleet had a very broad portfolio: elevators, dredgers, dredgers, barges, barges, screw steamers, paddle steamers. It is interesting to note that, along with the tugs Turkish and Storm, the poet Attila József served as a petty officer on board in 1920, when he was a young man.

The Atlantica report for the 1919 business year was very positive, except for the possible fate of the ships. Polnay systematically bought his way into a wide variety of businesses. Such investments included the Újpest dredging factory, the Érd steam-brickworks, and the Piszke quarry. With the help of these businesses, the Atlantica shipyard, the clerks' apartments and the canteen were built on the Háros- and Hunyadi Islands.

The ships acquired and the companies affiliated were all intended to make it easier for Polnay to build on the island of the City. As part of this, he connected the Háros and Hunyadi Islands to each other and to the mainland (Budafok) on the right bank of the Danube. And the raw materials he did not need, he sold on the market - 75 000 m3 was. On the now peninsula, Polnay also set up a public storage company and equipped the shipyard by purchasing the Schlick-Nicholson Mosquito Island shipyard's equipment. The trees on the island were felled and sold to the Szikra match factory in Budafok.

In addition to these, Atlantica Trust founded Terramare Transport Rt, Hydroflora Reed, Seed and Herb Factory Rt, Sideron Iron Trading Company, took over Duna-Rajna Trading Rt, Fővárosi Nyomda Rt and Continental Film Factory in Sashalm where raw film was produced for the film industry; and leased the Fotocines Italiana laboratory in Rome and the Astoria laboratory in Budapest. They also engaged in a commodity business, exporting domestic products and importing goods not available at home. Thus they became the sole Hungarian representative of a large Canadian asbestos mine. They leased the Herkules bitter water springs in Budafok, which had 17 wells in a fully equipped plant, and whose products they intended to export to America, Anglia, Italy and Africa. They organised coal imports through their sea-going ships. They attempted to finance a rural mill to export flour to Vienna, the Czech Republic and Germany. They exported walnuts to North America, but also other commodities such as salami, peppers, tinned peppers and sorghum. From Romania, they imported petrol and petroleum, and even transported live cattle by rail to Italy, where they were 'sold at a good price'.

In addition to this, Atlantica also began to engage in banking, such as stockbroking, bill discounting and foreign exchange, but Polnay's biggest deal was the founding and construction of the Lanaria postal factory on the island of Harbour, which drove the first nail into the coffin of Atlantica Trust with an investment of £300,000.

After the armistice of 3 November 1918, the former Atlantica ships were placed under the control of the Entente countries. After the Trianon peace treaty was signed in 1921, the Hungarian Government expropriated the Atlantica ships under the terms of Article XVI of Law 1922, promising compensation, and handed them over to the Reparation Commission, which gave the SS Atlantica to Yugoslavia and the other ships to Italy. Atlantica thus lost overnight its fleet, which had been built up with great care since 1907 and was the basis of all its financial development.

Polnay, aware of the serious consequences of the loss of the fleet, immediately entered into negotiations with the Italian government and succeeded in reaching an agreement. Under the terms of the agreement, in view of the interests of Fiuma, Atlantica Trust and the Italian Government set up a joint venture company, Fiumana Soceitá Anonima di Navigazione (Fiumana Shipping Company), with a share capital of ITL 1 000 000, in which the parties held 50-50% shares, the Italians providing the former Atlantica fleet (47 000 tonnes deadweight) and Atlantica managing the ships. In the new company, however, the names of the ships had to be Italianised. Thus Fiume became Fiumana, Count Khuen Héderváry became Atlantica, Count Serényi Béla became Danubio, Kossuth Ferencz became Alberto Fassini, Hungary became Ungheria and Szterényi became Budapest.

The ships generated some income in the early years, but the fleet was steadily depreciating as competitors operated much more modern steamers. Finally, the Great Depression gave Fiumana a reprieve. In the meantime, by the early 1930s, Atlantica Trust had become insolvent, because the Hungarian state refused to compensate the company for the expropriation of the property, nor to do anything about it, despite Polnay's constant requests to the ministries...

In another great feat, however, Polnay was able to found another entirely Hungarian shipping company in 1923. Elek Bíró writes about this. As Polnay had no money left, and currency difficulties made it impossible to resolve the matter, he proposed to the Harrimans that they should form a shipping company, the American Ship & Commerce Navigation Corporation. The shares in the company would be owned by Harriman and he would take over the fleet from Harriman, but he would not pay for it, i.e. it would be a simple change of flag. Harriman will transfer the ships to Oceana Navigation Ltd. for management. Half of Oceana's shares are owned by Harriman, the other half by Atlantica, the profits are used to make purchase payments to Harriman and when the agreed purchase price is settled by these payments the ships are transferred to Oceana. So Harriman eventually sells the ships, receives the purchase price and still owns half of the value of the ships and is part of a 50% earning deal. However, Atlantica, after paying the purchase price, owns half of the fleet without investing a penny. Meanwhile, it manages the ships and receives a commission of 3% for the transport".

The Oceana Shipping Company thus established started with great hopes, but the shipping depression of the second half of the decade left its mark on the company's operations, and with little revenue, Atlantica's financial deficit grew steadily due to claims on the government, and it was eventually unable to repay Harriman. The fleet consisted of the following ships: Oceana (8 100 tons deadweight), Pannonia (7 300 tons), Debrecen (6 500 tons), Balaton (6 100 tons), Alföld (5 100 tons), Háros (3 500 tons) and the original Atlantica fleet Morawitz. The ships were crewed by old Atlantians, so Hungarian sailors and engineers served under the Hungarian flag.

The Hungarian Statistical Yearbooks publish data on the operation of the Hungarian merchant marine between 1923 and 1939, but only the turnover of Oceana Shipping Ltd. is recorded for the period 1923-1929. In the light of this, it can be said that the company operated 7 ships (17 790 NRT capacity) between 1923 and 1926. Each year it made 40 to 42 voyages with its ships. It carried 236 800 tonnes in 1923, 220 000 tonnes in 1924, 235 600 tonnes in 1925 and 214 666 tonnes in 1926. Between 1928 and 1929, however, it had only one ship with a capacity of 2 595 NRT, carrying 27 711 tonnes of goods in 1928 and 55 193 tonnes in 1929, with 16 voyages a year. Oceana finally went into liquidation in 1929, before the outbreak of the economic crisis, which ended in 1943 when neither the Atlantica Trust nor the Harriman company, which had been hit hard by the 1929 crisis, were able to recover their claims.

To summarize what has been described so far, by the early 1930s the Atlantica group was essentially bankrupt, having lost all its profitable business, and the majority owner, the former Anglo-Austrian Bank, had sold what it could. There was only one step left to liquidate Atlantica Trust, the recovery of claims against the Hungarian state and the payment of the shareholders, but this was eventually lost in the labyrinths of Hungarian bureaucracy and can be assumed never to have been resolved. Jenő Polnay Tiszasülyi, the founder of the company, had to leave the management in disgrace. When he read in the Budapest Gazette of 25 April 1944 (Tuesday) the Ministerial Decree 1540/1944 on the termination of the employment and occupation of Jews in the intellectual professions, which came into force on that day, he informed the Company Court, as a law-abiding citizen, that he understood that this meant the end of his membership of the board of directors of Atlata.

Sources

Archives of the Capital of Budapest.

VII-2-e: Company court documents.

02042-1915 Atlantica Shipping Company (1907-1944).

11163-1920. Duna-Rajna Trading Company (1920-1924).

11959-1920. Textile and Carpet Factory Ltd (1920-1944).

16315-1921. Hydroflora Hungarian Reed, Cane and Herb Company (1921-1941).

16325-1921. Hungarian American Shipping Company (1921-1929).

16511-1922. Oceana Shipping Company (1922-1944).

17374-1922. Sideron Iron, Metal, Technical and Chemical Products Ltd (1922-1933).

18275-1922. Terra Mare Transport Ltd (1922-1933).

30226-1929. Zoltán Czukker Herkules Hungarian Bitter Water Spring Company (1929).

Hungarian National Archives. National Archives. Z. 1070. ATLANTICA Shipping Company (1887-1929).

Državni Arhiv u Rijeci - Rijeka State Archives. Maritime Authority records (DAR-46).

Hungarian Museum of Technology and Transport. Manuscript archive.

Népszava 11 April 1980, issue 6.

Róbert Bagdi - Norbert Hlbocsányi (2020). In György Kövér - Ágnes Pogány - Boglárka Weisz (eds.): Hálózat és Hierarchia. Hungarian Economic History Yearbook. Budapest. 465-486.

Gatshcer-Riedl, Gregor (2022): Steamer under the double eagle. Merchant ships and shipping companies in the Habsburg Monarchy. Berndorf.

Herczeg, Renáta - Prakfalvi, Endre (2016):The construction works of the Atlantica Shipping Company in the end days of the monarchy on Háros Island. Monument Protection 60. 3-4. nos. 207-230.

János Illésy - Béla Pettkó (eds.): Royal Books. Budapest. https://archives.hungaricana.hu/hu/libriregii/

Hungarian Compass: https://adt.arcanum.com/hu/collection/MagyarCompass/

TEXT: Hungarian Biographical Dictionary. https://mek.oszk.hu/00300/00355/html/

MSÉ (1919-1946): Hungarian Statistical Yearbooks. Published by the Royal Hungarian Central Statistical Office. https://adt.arcanum.com/hu/collection/MagyarStatisztikaiEvkonyv/

Márton Pelles (2019): History of Atlantica Shipping Company (1907-1918). XI. 1. 35-48.

Márton Pelles (2023):History of the Atlantica Trust (1906-1944).

789-814.

Márton Pelles (2024):The history of the Hungarian merchant navy between 1921-1945. Monograph, manuscript.

Márton Pelles - Gábor Zsigmond (2021):History of the Hungarian merchant navy of Rijeka 1868-1921.

János Schláth (2017): misplaced heritage. Szemelvények a magyar maritime history. From the history of Hungarian maritime history. The author's private publication.