Goldberger Sám. F. and sons ltd

The Goldberger family moved to Hungary in the 18th century. By the 19th century, the blue dye factory had already achieved significant results. In recognition of their role in domestic industry, the family was granted Hungarian nobility with the prefix "Buday" by Franz Joseph in 1867. However, even then, the business was still only a relatively modest blue dye factory. The expansion was initiated by Berthold Goldberger, who also took care of his successor in good time, sending his eldest son, Antal Goldberger, to study in Switzerland. Antal obtained a degree in chemical engineering there. He intended for his second son, Leo, to pursue a career in law. However, Antal died unexpectedly at a young age in 1899, so Leo had to join the family business.

Father and son jointly ran the company between 1899 and 1913, which was a very difficult period. The general crisis in the textile industry and the existence of competition meant a significant decline, which could only be offset by capital imports and developments. Therefore, the former general partnership was transformed into a joint-stock company in 1905, when Goldberger Sám. F. és Fiai Részvénytársaság (Goldberger Sám. F. and Sons Joint-Stock Company) was established, with Leó becoming the second-in-command of the company. The members of the board of directors were mostly family members.

Although the company obtained capital, it was slow to recover from the crisis. Between 1908 and 1914, the joint-stock company did not pay any dividends, and in 1911, the listing of its shares was suspended. In 1912, the company operated at a loss of 284,000 crowns, and in 1913, at a loss of 636,000 crowns.

However, the war brought an upturn, the business became profitable, and by early 1919 it had even begun to recover from the post-war collapse. However, the Council Republic intervened. Leó Goldberger moved to Switzerland with his family, but managed to save some of the company's assets, even at the cost of registering them in his own name. The fact that the company's assets had been transferred to Switzerland did not please one of the investors, Hazai Bank, which protested against the move. However, it was not only the bank that opposed the move. A member of the board of directors, Endre Aczél, filed a lawsuit against Goldberger for breach of trust, but Leó Goldberger won the case because he was able to prove with documents that he had acted in the interests of the company and not for his own personal gain.

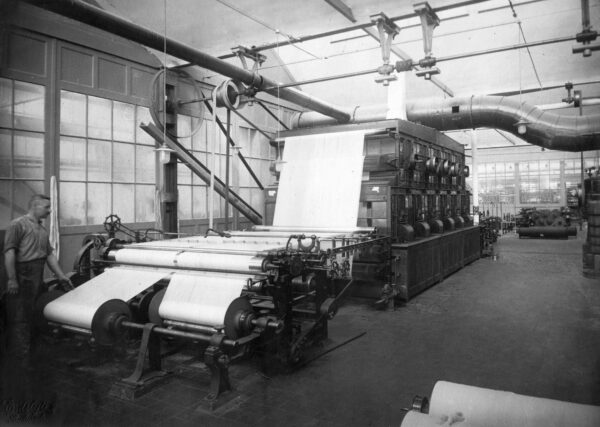

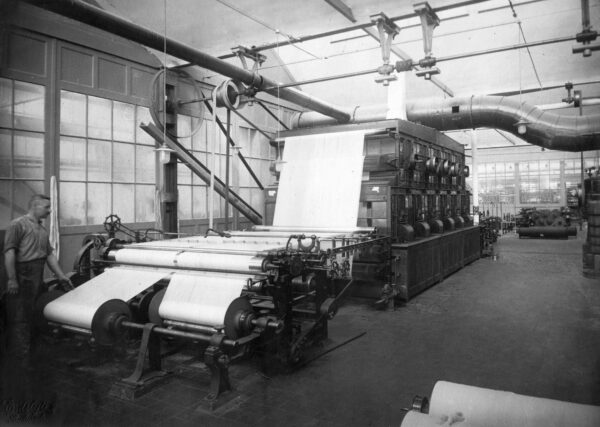

During his stay in Switzerland, Goldberger signed forward-looking contracts for the future and deepened his professional knowledge. Upon his return, he became president and CEO of the company in 1920, which established companies in Switzerland under the name Wespag and in London under the name ASCOLD. With the involvement of English investors, he built a spinning mill in Kelenföld. The aim was to create a truly vertical cotton factory that would not be dependent on suppliers. Following the investments, he modernised the machinery, enabling the factory to purchase the German Bemberg rayon patent and manufacture the product. This rayon was further developed at the Goldberger factory in Hungary, becoming the famous “Parisette” fabric, which brought significant financial success. Goldberger used the profits to buy out the foreign investors one by one, thus ensuring his independence.

Goldberger always looked for loopholes, but he did business fairly. The factory paid its bills punctually even during the most difficult times of the economic crisis, which Goldberger took special care to ensure. With the end of the crisis, production began to grow again, and in the 1930s, international expansion began, with half of the products finding buyers abroad. Goldberger made several trips, including one to the United States, from where he brought back production ideas and solutions. He did not travel alone, but constantly sent his colleagues on study trips abroad to increase their knowledge.

Inspired by what he saw abroad, he explored a number of ideas. However, not all of his ideas were successful. One such example was when Goldberger considered growing cotton at home, but preliminary calculations showed that it would not be a profitable venture.

Goldberger took great care of the company's PR activities, relationships and reputation, one manifestation of which was that the company was the only Hungarian exhibitor at the 1937 Paris World's Fair.

As the situation for Jews in Hungary deteriorated, Goldberger not only spoke out personally against the laws, but also tried to mitigate their effects in his factory. If necessary, he reduced managers' salaries to better comply with wage regulations. As long as he could, he employed Jewish employees who would have had to be dismissed due to the law, retiring them or trying to find them jobs elsewhere. The company gave those who were dismissed high severance pay.

In order to save the factory, Goldberger invited more and more renowned aristocrats and important public figures to join the company's board of directors, including Miklós Horthy Jr. Goldberger's efforts were successful: the factory was saved, and the company's production capacity was increased.

He was able to retain control of the company – with individual exemption – despite the provisions of the Jewish laws, although in 1940 Lieutenant Colonel Jenő Damó was appointed government commissioner to supervise the factory. Goldberger only received individual permission to run his company in 1942 on condition that he could not draw a salary.

During the war, Goldberger was already preparing for peace, making ambitious plans and preparing to revive his international connections. However, he did not establish any foreign companies or warehouses, which is why his family was unable to redeem him when he and several other family members were deported by the SS on 19 March 1944.

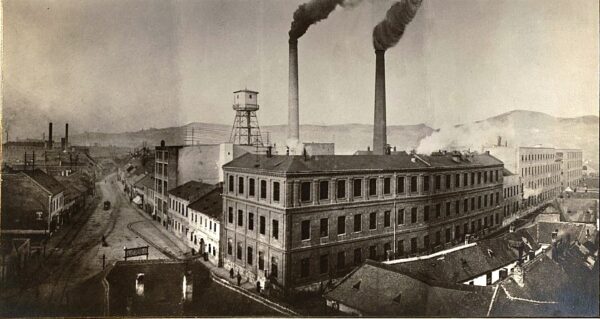

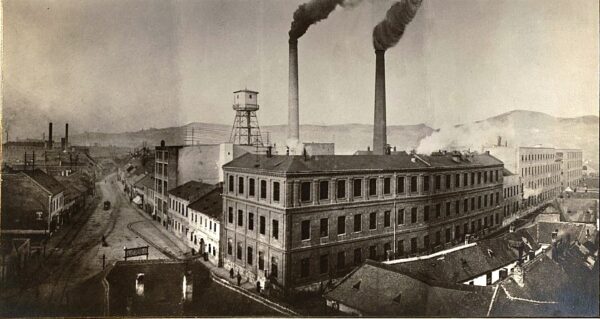

Leó Goldberger did not survive his imprisonment in Mauthausen, passing away on the day the camp was liberated. The company continued to operate as a private enterprise for a while, but was nationalised in 1948. In 1950, the business merged with other companies and continued its operations as Goldberger Textilnyomó Vállalat (Goldberger Textile Printing Company). The Kelenföld plant was made independent, and in 1955 the companies were merged again under the name Goldberger Textilművek, which was reorganised in 1963 into Budaprint Pamutnyomóipari Vállalat (Budaprint Cotton Printing Company) after merging with other companies (it was nicknamed „Panyova” from the abbreviation of this name, but many people continued to call it „Goli”). The state-owned company went bankrupt in 1989. Although a short-lived Budaprint Goldberger Textilművek Rt. was established, its liquidation began in 1992, and it was deleted from the company register in 1997. Leó Goldberger's daughter, Friderika, returned to Hungary in the early 1990s and tried to restart the factory with investors, but was unsuccessful. However, many of the company's former buildings, such as the iconic fire water tank, still stand in Óbuda today, and one of the buildings has recently been converted into a modern co-working space (Puzl CowOrKing).

The memory of the Goldberger factory is preserved by the Goldberger Textile Industry Collection, housed in the historic building of the Goldberger factory in Óbuda.

Interesting facts

In 1929, an event took place in front of a large audience at the Vigadó in Pest, where 500 girls and women from Pest paraded one by one in dresses made from Parisette fabric. Leó Goldberger was on the jury of the competition, which was actually a kind of beauty contest. Several of the contestants had to be disqualified because it was discovered that their dresses were not made from Parisette fabric. It turned out that some shops were selling fake Parisette fabric because the product was so popular.

Among Hungarian factories, Goldberger provided one of the most extensive social networks. Not only did it operate various welfare funds, nurseries, medical clinics and pension funds, but it also ensured that the air in the factories was constantly purified. What is more, it was the first in Hungary to operate a work psychology laboratory under the supervision of the Hungarian Psychological Association.

Literature:

- Ildikó Guba: “Death is not a programme” The life of Leó Buday-Golberger Óbuda Museum 2014

- Miklós Vécsey: One Hundred Notable Hungarians (Budapest, 1931)

- László Kállai: The 150-year-old Goldberger factory. History of the Hungarian textile industry 1784-1934 (Budapest, 1935)

Date of establishment: 1905

Date of cessation: 1950

Founders: Leó Goldberger, Berthold Goldberger

Decisive leaders:

1905-1944 | Leó Goldberger |

Main activity: textile production

Locations:

Óbuda | |

Kelenföld |

Author: by Domonkos Csaba

Date of establishment: 1905

Founders: Leó Goldberger, Berthold Goldberger

Decisive leaders:

1905-1944 | Leó Goldberger |

Main activity: textile production

Main products are not set

Seats are not configured

Locations:

Óbuda | |

Kelenföld |

Main milestones are not set

Author: by Domonkos Csaba

Goldberger Sám. F. and sons ltd

The Goldberger family moved to Hungary in the 18th century. By the 19th century, the blue dye factory had already achieved significant results. In recognition of their role in domestic industry, the family was granted Hungarian nobility with the prefix "Buday" by Franz Joseph in 1867. However, even then, the business was still only a relatively modest blue dye factory. The expansion was initiated by Berthold Goldberger, who also took care of his successor in good time, sending his eldest son, Antal Goldberger, to study in Switzerland. Antal obtained a degree in chemical engineering there. He intended for his second son, Leo, to pursue a career in law. However, Antal died unexpectedly at a young age in 1899, so Leo had to join the family business.

Father and son jointly ran the company between 1899 and 1913, which was a very difficult period. The general crisis in the textile industry and the existence of competition meant a significant decline, which could only be offset by capital imports and developments. Therefore, the former general partnership was transformed into a joint-stock company in 1905, when Goldberger Sám. F. és Fiai Részvénytársaság (Goldberger Sám. F. and Sons Joint-Stock Company) was established, with Leó becoming the second-in-command of the company. The members of the board of directors were mostly family members.

Although the company obtained capital, it was slow to recover from the crisis. Between 1908 and 1914, the joint-stock company did not pay any dividends, and in 1911, the listing of its shares was suspended. In 1912, the company operated at a loss of 284,000 crowns, and in 1913, at a loss of 636,000 crowns.

However, the war brought an upturn, the business became profitable, and by early 1919 it had even begun to recover from the post-war collapse. However, the Council Republic intervened. Leó Goldberger moved to Switzerland with his family, but managed to save some of the company's assets, even at the cost of registering them in his own name. The fact that the company's assets had been transferred to Switzerland did not please one of the investors, Hazai Bank, which protested against the move. However, it was not only the bank that opposed the move. A member of the board of directors, Endre Aczél, filed a lawsuit against Goldberger for breach of trust, but Leó Goldberger won the case because he was able to prove with documents that he had acted in the interests of the company and not for his own personal gain.

During his stay in Switzerland, Goldberger signed forward-looking contracts for the future and deepened his professional knowledge. Upon his return, he became president and CEO of the company in 1920, which established companies in Switzerland under the name Wespag and in London under the name ASCOLD. With the involvement of English investors, he built a spinning mill in Kelenföld. The aim was to create a truly vertical cotton factory that would not be dependent on suppliers. Following the investments, he modernised the machinery, enabling the factory to purchase the German Bemberg rayon patent and manufacture the product. This rayon was further developed at the Goldberger factory in Hungary, becoming the famous “Parisette” fabric, which brought significant financial success. Goldberger used the profits to buy out the foreign investors one by one, thus ensuring his independence.

Goldberger always looked for loopholes, but he did business fairly. The factory paid its bills punctually even during the most difficult times of the economic crisis, which Goldberger took special care to ensure. With the end of the crisis, production began to grow again, and in the 1930s, international expansion began, with half of the products finding buyers abroad. Goldberger made several trips, including one to the United States, from where he brought back production ideas and solutions. He did not travel alone, but constantly sent his colleagues on study trips abroad to increase their knowledge.

Inspired by what he saw abroad, he explored a number of ideas. However, not all of his ideas were successful. One such example was when Goldberger considered growing cotton at home, but preliminary calculations showed that it would not be a profitable venture.

Goldberger took great care of the company's PR activities, relationships and reputation, one manifestation of which was that the company was the only Hungarian exhibitor at the 1937 Paris World's Fair.

As the situation for Jews in Hungary deteriorated, Goldberger not only spoke out personally against the laws, but also tried to mitigate their effects in his factory. If necessary, he reduced managers' salaries to better comply with wage regulations. As long as he could, he employed Jewish employees who would have had to be dismissed due to the law, retiring them or trying to find them jobs elsewhere. The company gave those who were dismissed high severance pay.

In order to save the factory, Goldberger invited more and more renowned aristocrats and important public figures to join the company's board of directors, including Miklós Horthy Jr. Goldberger's efforts were successful: the factory was saved, and the company's production capacity was increased.

He was able to retain control of the company – with individual exemption – despite the provisions of the Jewish laws, although in 1940 Lieutenant Colonel Jenő Damó was appointed government commissioner to supervise the factory. Goldberger only received individual permission to run his company in 1942 on condition that he could not draw a salary.

During the war, Goldberger was already preparing for peace, making ambitious plans and preparing to revive his international connections. However, he did not establish any foreign companies or warehouses, which is why his family was unable to redeem him when he and several other family members were deported by the SS on 19 March 1944.

Leó Goldberger did not survive his imprisonment in Mauthausen, passing away on the day the camp was liberated. The company continued to operate as a private enterprise for a while, but was nationalised in 1948. In 1950, the business merged with other companies and continued its operations as Goldberger Textilnyomó Vállalat (Goldberger Textile Printing Company). The Kelenföld plant was made independent, and in 1955 the companies were merged again under the name Goldberger Textilművek, which was reorganised in 1963 into Budaprint Pamutnyomóipari Vállalat (Budaprint Cotton Printing Company) after merging with other companies (it was nicknamed „Panyova” from the abbreviation of this name, but many people continued to call it „Goli”). The state-owned company went bankrupt in 1989. Although a short-lived Budaprint Goldberger Textilművek Rt. was established, its liquidation began in 1992, and it was deleted from the company register in 1997. Leó Goldberger's daughter, Friderika, returned to Hungary in the early 1990s and tried to restart the factory with investors, but was unsuccessful. However, many of the company's former buildings, such as the iconic fire water tank, still stand in Óbuda today, and one of the buildings has recently been converted into a modern co-working space (Puzl CowOrKing).

The memory of the Goldberger factory is preserved by the Goldberger Textile Industry Collection, housed in the historic building of the Goldberger factory in Óbuda.

Interesting facts

In 1929, an event took place in front of a large audience at the Vigadó in Pest, where 500 girls and women from Pest paraded one by one in dresses made from Parisette fabric. Leó Goldberger was on the jury of the competition, which was actually a kind of beauty contest. Several of the contestants had to be disqualified because it was discovered that their dresses were not made from Parisette fabric. It turned out that some shops were selling fake Parisette fabric because the product was so popular.

Among Hungarian factories, Goldberger provided one of the most extensive social networks. Not only did it operate various welfare funds, nurseries, medical clinics and pension funds, but it also ensured that the air in the factories was constantly purified. What is more, it was the first in Hungary to operate a work psychology laboratory under the supervision of the Hungarian Psychological Association.

Literature:

- Ildikó Guba: “Death is not a programme” The life of Leó Buday-Golberger Óbuda Museum 2014

- Miklós Vécsey: One Hundred Notable Hungarians (Budapest, 1931)

- László Kállai: The 150-year-old Goldberger factory. History of the Hungarian textile industry 1784-1934 (Budapest, 1935)