Ganz & Comp. electric machine, railway, carriage-manufacturing & ship-building Co. Ltd.

1844-1869: the beginnings

In the reform era, there was no modern machine building in Hungary. In 1841, Abraham Ganz, a Swiss foundry master, who had gained experience in Swiss, French and Italian factories and had been working in Vienna since 1839, found employment in Hungary in the form of the assembly and maintenance of the machines of the new Hengermalom mill. He managed the foundry of Hengermalom, the country's first urban foundry independent of the ironworks, and became self-employed in 1844. His small foundry, set up in Óbuda, mainly produced various articles for the population and public buildings (e.g. sewer and water pipes, gratings, door and window panes, buckets, sinks, stoves). He supported the War of Independence by producing cannons and cannonballs. In 1851, he joined the mining and ironworks of Frigyes in Saska (Banat) to supply the foundry with raw materials, but he sold this investment a few years later. In the 1950s, accelerating railway investment in central Europe created an expanding market for Ganz's patented bark-cast railway wheels, which had a longer life than competing products and were competitive until the advent of the Griffin wheel (a further development of the bark-cast, invented by John Burn in 1812, and applied to railway wheels by means of cup or coquille casting. In 1855, Abraham Ganz patented the bark casting, and in 1857 a further development of this process specifically for railway wheels). In 1859, Abraham Ganz, who was also responsible for the commercial and technical management of the rapidly growing company and its business acquisition activities, won three German engineers, Ödön Vilmos Krempe, Antal Eichleiter and András Mechwart, to take over the technical management of the plant.

In December 1867, the Ganz heirs (Ganz's brothers and their minor children) and the factory's leading employees (Eichleiter, Mechwart and Keller Ulrich, accountant) transformed the company into a partnership under the name Ganz & Partner. Recognising the opportunities for economic recovery created by the Reunification, the company was bought by merchants and bankers and transformed into a limited company, with Eichleiter as vice-president, Mechwart as technical director and Keller as commercial director.

1869-1911: Ganz and Company Iron Foundry and Machine Works Ltd.

The crisis that unfolded in 1873 set back railway construction outside Hungary as well, shaking Ganz's position. Eichleiter and Keller left the country in 1875 and Mechwart András took over the management of the company. Mechwart put the company on a new growth path by producing cylinders, building up the electrotechnical business and stabilising the factory's turnover by further expanding the range of products (war materials such as artillery shells, ammunition carriages, railway traffic aids such as turntables, all kinds of castings for buildings and utilities). It was then that the company was transformed from a foundry into a real machine factory, with a machine, wagon and electrical engineering plant.

The Mechwart rolling mill and the millwright class

In 1876, Mechwart patented his invention, which improved on the Wegmann cylinder using bark-casting technology. The design, which used grooved steel rollers, was not only one of the key export successes of the Hungarian milling industry in the dual-industry era, but its various versions were also used as crushing and grinding machines by distilleries, but also by construction and machinery companies, for example for grinding cement and ores. Rolling mills found a market on all five continents. In addition to rolling mills, Ganz also produced complete milling equipment (grain cleaning and sorting machines, elevators, weighing scales, conveyor pulleys, etc.).

Developing the rail transport business

In 1880, the company bought the First Hungarian Railway Carriage Factory Ltd. (its more commonly used company name is "First Hungarian Carriage Factory Ltd."), in the foundation of which Ábrahám Ganz had participated in 1867, and built up his carriage production on its premises (Budapest X., With the boom in Hungarian railway construction, wagon production not only increased in quantity (e.g. in 1889 there were already 2,571 wagons produced), but also the production of passenger cars increased, and the number of wagon types increased (e.g. From the 1890s, Ganz also produced trams, steam and electric motor cars, and later electric locomotives.

The acquisition of the Mecenzev iron foundry and iron ore mine near Košice in the early 1870s and the Petrova Gora mine and smelter in Zagreb County in 1891, as well as the establishment of the Polish machine factory in Ratibor (1869, serving German, Polish and northern Russian areas) helped to expand the market for railway wheels, wagons and other machinery and increased its profitability.

The development of the electrical engineering business

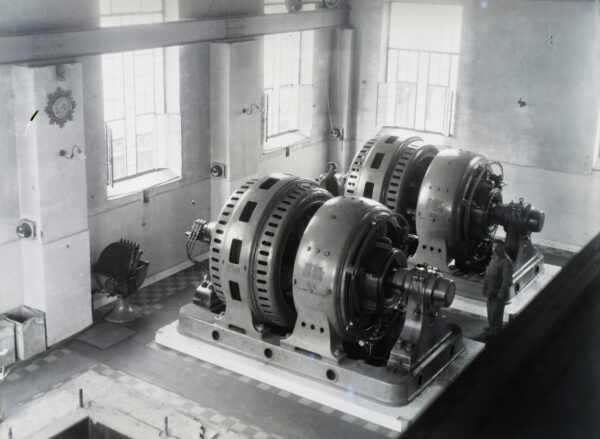

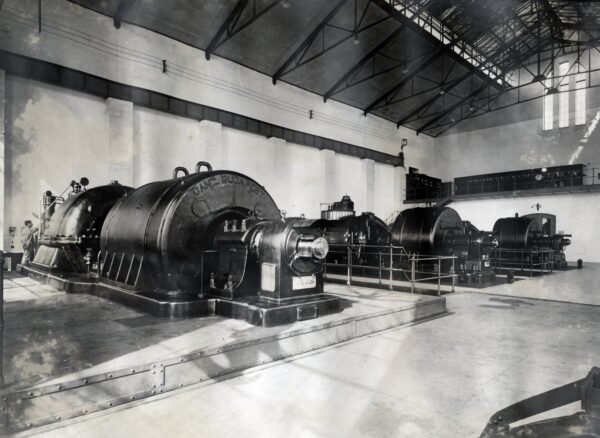

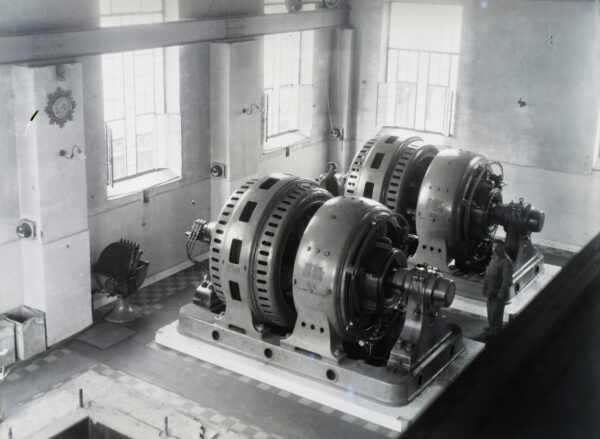

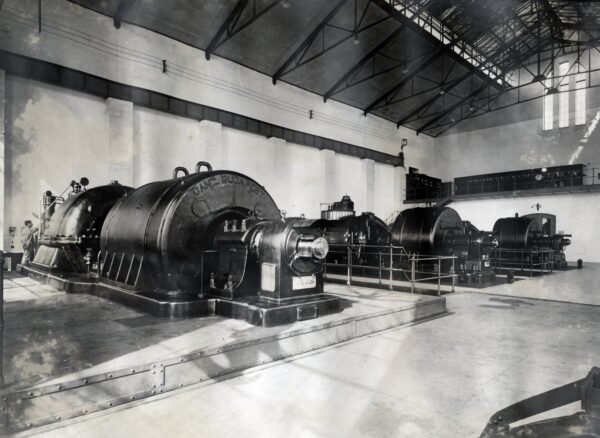

Based on the experience of the Paris World Fair of 1878, Mechwart's general manager employed Károly Zipernowszky to organise Ganz's electrotechnical department, which established itself in the manufacture of DC dynamos, arc lamps, etc. The most famous creation of the engineering trio of Miksa Déri - Ottó Titusz Bláthy - Károly Zipernowszky was the alternating current electrical power distribution system with iron-core transformers, an improvement on the Gaulard & Gibbs system (1885). Its main advantage over Edison's direct current system was its ability to transmit power economically over greater distances.

By the mid-1890s, the Ganz factory had grown to become the largest electrical engineering company in the Austro-Hungarian Empire with domestic roots (i.e. it was not a subsidiary of a company outside the Monarchy), and by the turn of the century alone it had built some 200 power plants outside Hungary, including the Societa Edison power plant in Milan, the power plants in Turin, Grenoble, Livorno, Treviso, Innsbruck, Caransebes and Timisoara. Its most important markets are in the western part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where Ganz, together with the Hungarian Mortgage Bank and the Unionbank of Vienna, founded in 1889 Internationale Elektrizitäts-A.-G. as a financing company to build up its market and Italy, where it established a market presence with a network of engineering offices and the Societa generale per lo Sviluppo delle Imprese elettriche in Italia ("Sviluppo") with a financing company (shareholders in addition to Ganz: Magyar Általános Hitelbank, Creditanstalt, S.M. v. Rothschild, Banca Commerciale of Milan and Gesellschaft für elektrische Unternehmungen ("Gesfürel") of Berlin). Other major markets for Ganz were Russia and South America, but it also exported its electrical engineering products from Western and South-Eastern Europe to Australia.

The 1880s and 90s saw a fierce battle between the different energy transmission systems. Ganz was forced into years of litigation to defend the validity of its patents against AEG and Siemens in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy and Germany. The lengthy litigation was settled, but it proved that Ganz's capital strength and personnel capacity meant that it could only build lasting and significant markets and defend its patents in the Monarchy and Italy.

From 1892 Ganz also manufactured electric vehicles, e.g. mining locomotives, and participated in the electrification of urban railways (1892 Budapest-Újpest-Rákospalotai Electric Railway Ltd, Founders: Ganz, Magyar Ipar und Kereskedelmi Bank, Wiener Bankverein and Jakob Landau Bankhaus Berlin). In 1894-95, the Hungarian General Credit Bank bought up the majority of Ganz's shares.

Ganz also played a part in the development of large-scale railway traction. Kálmán Kandó's three-phase system was tested on the Val Tellina line in Italy. Due to the financial loss caused by the protracted (1898-1902) development and the expected lack of domestic orders, Ganz did not support further developments. Kando and his team were employed by the American company Westinghouse in Italy, where their system electrified a large part of the railways, which Sistema Italiana in the history of technology.

In 1906, Ganz's electrotechnical division became an independent joint-stock company under the name Ganz-éle Villamossági Gyár Rt. with the participation of the German AEG, but the following year - partly due to political pressure - the German owner was bought out by Hitelbank.

By the mid-1890s the Ganz product range has been significantly expanded. In addition to railway wheels, crossings and guide rails, mill rollers, bark-cast artillery shells, architectural and engineering parts, fittings, mainly pipes, the foundry also produced metal and steel castings from the late 1880s. Mechanical engineering included the following product groups: cylinders, cranes, railway switchgears, turntables and shunting gears, Mechwart friction clutches, water turbines for mills, baths, sawmills, post, furniture, paper and iron works, then for driving electrical machinery, pulp and paper mill equipment, and from the 1890s, engines (gas, petroleum, electric). In 1887, Ganz bought the bankrupt Leobersdorf Machinery Works Ltd., which produced, among other things, pulp and paper machinery and war material.and modernised it and set up the production of pulp and paper machinery there. With the wagon factory and the electrical engineering business (design and manufacture of lighting systems and complete power stations, hydro generators from 1897, turbo-generators from 1903), Ganz developed into one of Hungary's most prestigious factories in many branches of foundry, mechanical and electrical engineering.

1911-1929: Ganz and Company Danubius Machine, Waggon and Shipyard Ltd.

In 1911, in preparation for the war, Ganz bought all the shares of Danubius Ship and Machine Works Ltd. (formerly Danubius-Schoenichen-Hartmann, a united ship and machine works Ltd.), which was also owned by the Hungarian General Credit Bank. The merger eliminated the competition between the two factories, e.g. in the production of wagons, and allowed better use of the sites. Danubius was the most important shipbuilding factory in the country, with plants in Budapest (Újpest), Fiume and Portore; since 1906 it had also built warships to the designs of the Stabilimento Tecnico in Trieste. Ganz-Danubius modernised the design and production of warships through Ganz's experience in engine and motor production, British and German patents and manufacturing investments, and thus succeeded in winning the quota orders for Hungary from the Monarchy's naval programme.

This means that in 1912, in Rijeka, the SMS Heligoland fast cruiser and three Tatra-class destroyers in Portore: the SMS Tatras, the SMS Lake Balaton and the SMS Csepel. in 1913 in Fiume, the SMS Novara fast cruiser and three more Tatra-class destroyers in Portoré: the SMS Lika, the SMS Orjen and the SMS Triglav. On 17 January 1914, in Fiume, the pinnacle of Hungarian warship construction at the time, the SMS St Stephen's the battleship and the electric sea-testing submarine built for the Berlin Aquarium, the Loligot.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Ganz was one of the largest companies in the country, with about 10,000 workers, foundries in Budapest and Petrova Gora, machine factories in Budapest, Ratibor and Leobersdorf, a wagon factory in Budapest, shipyards in Budapest, Fiume and Portore, an electrical engineering factory in Budapest, and a well-established brand name abroad.

International cooperation during the First World War

In 1912, Ganz, Weiss Manfréd and the Hungarian General Credit Bank founded the Hungarian Aircraft Factory Ltd. with the participation of the businessman Camillo Castiglioni from Trieste and the Austrian Lohner Works, who played an important role in the creation of the Austrian aircraft industry. Hansa und Brandenburgische Flugzeugwerke became one of the largest manufacturers in the Monarchy after the capital investment and the transfer of its structural drawings, and after the reorganisation of the factory (1916). In 1916, Ganz and Österreichische Fiat Werke founded Ganz-Fiat Magyar repülőgépmotorgyár rt. Thus, during the war, Ganz served the Monarchy's war effort by manufacturing and repairing road and rail transport vehicles (e.g. military trucks under Fiat and later Büssing licences, disinfection and artillery equipment), war and cargo ships, aircraft and aircraft engines, cast iron grenades, ship and aircraft power equipment.

1920s

The loss of the war, the financial damage caused by the Romanian occupation, the break-up of the Monarchy and the significant loss of territory in Hungary triggered a transformation crisis in the Hungarian machinery industry. The production capacity of the machinery industry, which was heavily concentrated in the capital, far exceeded the reduced consumption of the rest of the country, which was financially depleted. Access to export markets became more difficult, as the ubiquitous expansion of machinery production during the war led to increased competition, depressed prices and the imposition of new trade barriers.

After the First World War, Ganz's shipyard in Fiume was transformed into a separate joint stock company (Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro Societa Anonima Fiume) with the participation of Banca Italiana di Sconto and Societa Alti Torni Fonderie ed Acciaieni di Terni Anonima, while the Portore plant continued to operate as a Yugoslavian independent company (Jugoslavenska Brodogradilista d.d. Portore).

One of the most important consequences of the country's lack of capital for Ganz was that the Kando second main line electrification system was finally tested in operation with a British government loan, through the joint efforts of British and Hungarian companies. This involved the electrification of the Budapest-Hegyeshalom line and the construction of the Tatabánya power station between 1928 and 1932, the latter supplying three counties in addition to the needs of the railway. Despite the demonstration of the viability of the Kandó system, however, railway electrification in Hungary was halted for decades.

Another important consequence of the lack of capital was the slowdown in the development of the electrical engineering business, which was then operating as a separate company. Between the two world wars, the increasing size of the electrification projects required significant product development (e.g. turbine capacity) and financial backing (investment loans for product development and potential customers), which the company could not keep up with due to the decline in the equity of Ganz's own capital and the financial situation of the Hungarian and potential Austrian banks. Ganz's competitive position was characterised by the fact that it was not a member of the cartel uniting the world's leading manufacturers of electrical machinery (International Electric Association, 1930, members: International General Electric, International Westinghouse Electric Corp., four British manufacturers, AEG, Siemens and the Swiss Brown-Boveri & Cie.), but in 1934 it was able to join the cartel of the largest European electricity meter manufacturers (Accord de Paris, 1933), which had been formed the previous year.

The traditional products shipped to the neighbouring countries as reparations postponed the need to renew the Ganz-Danubius product range for a few years. However, low levels of public investment in infrastructure and declining export shipments and profits led to the company's indebtedness. In the second half of the 1920s, Ganz-Danubius merged four smaller machine factories to reduce competition (Schlick-Nicholson Gépgyár rt., Gép- und Vasútfelszerelési Rt., Erste Magyar Nährógép- und Kerékpárgyár rt., Dr. Lipták & Társa építési és Társa vasipari rt.), and in 1929 Ganz Electricity Rt. merged with the parent company.

1929-1946: Ganz & Co. Danubius Electricity, Machine, Waggon and Shipyard Ltd.

In addition to mergers, the company's management also sought other ways out of the transformation crisis and later the global economic crisis. First, Ganz was a leading or significant member of major cartels in the industry. One of the declared aims of these was to help members adapt to the market conditions created by the new national borders. They were of practical use mainly in helping to weather the Great Depression by preventing to some extent a sharp fall in prices and, to a lesser extent, by facilitating product specialisation between members.

On the other hand, the company attracted fresh capital: in 1930, General Electric and the German AEG, within a few years AEG alone became the owner of 25% of Ganz's shares. Under agreements with foreign owners, Ganz's electrical plant was allowed to use their patents with territorial restrictions, and the export of the electrical plant was restricted and the export of mechanical machinery such as diesel engines to South America was subsidised.

In the long term, the most significant element of crisis management has been product development. The excellent diesel engines designed by György Jendrassik were mass-produced by Ganz from the late 1920s. In the 1930s, in addition to the electrification of the railways, the use of diesel locomotives or motor coaches, which required less investment, was another way of replacing steam traction. Motor coaches with Jendrassik engines were suitable for cost-effective supply to the rural areas of the new Hungary. MÁV supported product development by ordering several different types. Ganz motor coaches performed well in suburban traffic in Western Europe and in the mountainous areas of Yugoslavia. Using this experience, Ganz played a leading role in the motorisation of railways in Argentina before the outbreak of the World War, and planned to enter the markets of less industrially developed, large countries (South America, Africa (e.g. Egypt, Rhodesia)).

Hungarian Railcar Test Drive (1938) Source: NFI Film Archive

In order to boost trade with Egypt and the Middle East, Ganz designed a low-draft, high-stability Danube cruiser with Jendrassik engines, but only six were built by 1941.

The launching of the "Szeged" (1936) Source: NFI Film Archive

It was mainly the export success of diesel engines and motor cars, investments in transport and electricity in the second half of the 1930s, followed by investments in the country in the run-up to war, and the halving of the share price in 1938, that enabled Ganz to stabilise its financial situation, which had deteriorated further in the late 1930s due to the shocks of the Great Depression.

Second World War

During the Second World War, the Ganz Wagon and Machine Works was more involved in military production. The Ganz Electricity Factory carried out repairs and extensions to various industrial plants and power stations providing public lighting, supplied electric locomotives, electric motor cars, large transformers, electrical equipment for transport companies; its largest work was the manufacture of equipment for the new Matravaidek Power Station.

During the war, Ganz's capital was increased several times, and the shares were taken over by the Hitelbank in exchange for the company's debts. Since AEG did not buy any of the new shares, its share in Ganz's capital steadily decreased. In 1943, Hitelbank bought back AEG's shares in Ganz, and the company was again fully Hungarian-owned.

1945-1989

During the war, Ganz suffered extensive damage, with the electricity factory being the worst affected.

In 1946, to support the reconstruction of the country, the Hungarian government nationalised the mines, electricity distribution companies and five strategic enterprises, including Ganz, and placed them under the unified control of the newly organised Heavy Industry Centre. In 1949, the Ganz factory was split into independent state-owned companies (Ganz Wagon and Machine Works, Ganz Electricity Works, Ganz Shipyard, Ganz Switch and Appliance Works, Ganz Power Meter Works). In 1959, Ganz Wagon and Machine Works was merged with MÁVAG, which operated under the name GANZ-MÁVAG Locomotive, Wagon and Machine Works until the end of 1988.

After the regime change

Several smaller companies were established on the ruins of the bankrupt Ganz-MÁVAG (Ganz Gépgyár Vállalat, Ganz Motor Kft., Ganz Energetikai Gépgyártó Kft.) Ganz's mechanical engineering activities were continued by Ganz Motor Kft., Ganz Vasúti Forgóváz- és Járműgyártó Kft., Ganz Motor Kft., Ganz Vasúti Forgóváz- és Járműgyártó Kft., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt, Ganzeg Kft. and Ganz Hydro Kft., with the following products: railway vehicles, components and parts, railway transmission equipment, diesel and gas engines, generating sets, machinery and steel structures, automatic irrigation equipment, water supply systems. The Ganz Electricity Factory tradition is continued by Ganz Transformer and Electrical Rotating Machinery Manufacturing Ltd., which manufactures transformers and related steel structures, motors and generators.

A large-scale landscaping programme started in 2001 at the former Ganz factory in Buda. The Millenáris Park, which preserves parts of the former industrial monuments, was completed in its current form in 2022.

Sources

Berlász, Jenő, The first half century of the Ganz factory 1845-1895, in Tanulmányok Budapest múltjából (1957) 12, pp. 349-458.

Boross, Elizabeth A., Inflation and industry in Hungary 1918-1929. Haude & Spener, Berlin, 1994.

Hidvégi, Mária, Connecting to the world market. Hungary's leading electrical engineering companies 186-1949. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2016.

Hidvégi, Mária, The Ganz-Jendrassik diesel cars in Argentina, in AETAS 29 (2014) 4, pp. 45-64.

Hidvégi, Mária, Crises and Responses: government policies and the Machine-building Cartels in Hungary, 1919-1949, Enterprise and Society 20 (March 2019) 1, 89-131.

Pogány, Ágnes, Bankers and business partners. The Hungarian General Credit Bank and its corporate clients between the two world wars, in. 55-66.

Rév, Pál, The circumstances of the development of the Hungarian aircraft industry, in Czére Béla (ed.), Yearbook of the Museum of Transport 2. 1972-1973. Közlekedési Dokumentációs Vállalat, Budapest, 1974, pp. 221-233.

István Szécsey, Ganz railway vehicles from 1920 to 1959. Budapest, Indóház Kiadó, 2013.

Szekeres, József, The History of Shipbuilding in Újpest I (1863-1911) and II (1912-1944), in Studies on the Past of Budapest (1961) 14, pp. History of History of Budapest, History of History in Historical Perspectives (1961), pp. 483-531 and (1963) 15, pp. 637-693.

Szekeres, József; Árpád Tóth, The History of the Klement Gottwald (Ganz) Electricity Factory. Közgazdasági és Jogi Kiadó, Budapest, 1962.

The different volumes of the Great Hungarian Compass (formerly Mihók's)

Intenet sources:

Resch, Andreas, The beginning of aircraft construction in Austria.

https://www.ganz-holding.hu/ceginformacio

https://www.ganzelectric.com/rolunk/

https://www.gtkb.hu/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14&Itemid=255&lang=hu

Founded in 1929

Date of cessation: 1948

Founders: Ganz and Co-Danubius Machine, Wagon and Shipyard Ltd.; Ganz Electricity Ltd.; First Hungarian Sewing Machine and Bicycle Factory Ltd.

Securities issued:

| Ganz and Co. electrical, machinery, wagons and shipbuilding ltd |

Main activity: mechanical engineering

Seats:

1929-1948 | Budapest |

Author: by Hidvégi Mária

Founded in 1929

Founders: Ganz and Co-Danubius Machine, Wagon and Shipyard Ltd.; Ganz Electricity Ltd.; First Hungarian Sewing Machine and Bicycle Factory Ltd.

Determinant drivers are not set

Main activity: mechanical engineering

Main products are not set

Seats:

1929-1948 | Budapest |

Locations are not set

Main milestones are not set

Author: by Hidvégi Mária

Ganz & Comp. electric machine, railway, carriage-manufacturing & ship-building Co. Ltd.

1844-1869: the beginnings

In the reform era, there was no modern machine building in Hungary. In 1841, Abraham Ganz, a Swiss foundry master, who had gained experience in Swiss, French and Italian factories and had been working in Vienna since 1839, found employment in Hungary in the form of the assembly and maintenance of the machines of the new Hengermalom mill. He managed the foundry of Hengermalom, the country's first urban foundry independent of the ironworks, and became self-employed in 1844. His small foundry, set up in Óbuda, mainly produced various articles for the population and public buildings (e.g. sewer and water pipes, gratings, door and window panes, buckets, sinks, stoves). He supported the War of Independence by producing cannons and cannonballs. In 1851, he joined the mining and ironworks of Frigyes in Saska (Banat) to supply the foundry with raw materials, but he sold this investment a few years later. In the 1950s, accelerating railway investment in central Europe created an expanding market for Ganz's patented bark-cast railway wheels, which had a longer life than competing products and were competitive until the advent of the Griffin wheel (a further development of the bark-cast, invented by John Burn in 1812, and applied to railway wheels by means of cup or coquille casting. In 1855, Abraham Ganz patented the bark casting, and in 1857 a further development of this process specifically for railway wheels). In 1859, Abraham Ganz, who was also responsible for the commercial and technical management of the rapidly growing company and its business acquisition activities, won three German engineers, Ödön Vilmos Krempe, Antal Eichleiter and András Mechwart, to take over the technical management of the plant.

In December 1867, the Ganz heirs (Ganz's brothers and their minor children) and the factory's leading employees (Eichleiter, Mechwart and Keller Ulrich, accountant) transformed the company into a partnership under the name Ganz & Partner. Recognising the opportunities for economic recovery created by the Reunification, the company was bought by merchants and bankers and transformed into a limited company, with Eichleiter as vice-president, Mechwart as technical director and Keller as commercial director.

1869-1911: Ganz and Company Iron Foundry and Machine Works Ltd.

The crisis that unfolded in 1873 set back railway construction outside Hungary as well, shaking Ganz's position. Eichleiter and Keller left the country in 1875 and Mechwart András took over the management of the company. Mechwart put the company on a new growth path by producing cylinders, building up the electrotechnical business and stabilising the factory's turnover by further expanding the range of products (war materials such as artillery shells, ammunition carriages, railway traffic aids such as turntables, all kinds of castings for buildings and utilities). It was then that the company was transformed from a foundry into a real machine factory, with a machine, wagon and electrical engineering plant.

The Mechwart rolling mill and the millwright class

In 1876, Mechwart patented his invention, which improved on the Wegmann cylinder using bark-casting technology. The design, which used grooved steel rollers, was not only one of the key export successes of the Hungarian milling industry in the dual-industry era, but its various versions were also used as crushing and grinding machines by distilleries, but also by construction and machinery companies, for example for grinding cement and ores. Rolling mills found a market on all five continents. In addition to rolling mills, Ganz also produced complete milling equipment (grain cleaning and sorting machines, elevators, weighing scales, conveyor pulleys, etc.).

Developing the rail transport business

In 1880, the company bought the First Hungarian Railway Carriage Factory Ltd. (its more commonly used company name is "First Hungarian Carriage Factory Ltd."), in the foundation of which Ábrahám Ganz had participated in 1867, and built up his carriage production on its premises (Budapest X., With the boom in Hungarian railway construction, wagon production not only increased in quantity (e.g. in 1889 there were already 2,571 wagons produced), but also the production of passenger cars increased, and the number of wagon types increased (e.g. From the 1890s, Ganz also produced trams, steam and electric motor cars, and later electric locomotives.

The acquisition of the Mecenzev iron foundry and iron ore mine near Košice in the early 1870s and the Petrova Gora mine and smelter in Zagreb County in 1891, as well as the establishment of the Polish machine factory in Ratibor (1869, serving German, Polish and northern Russian areas) helped to expand the market for railway wheels, wagons and other machinery and increased its profitability.

The development of the electrical engineering business

Based on the experience of the Paris World Fair of 1878, Mechwart's general manager employed Károly Zipernowszky to organise Ganz's electrotechnical department, which established itself in the manufacture of DC dynamos, arc lamps, etc. The most famous creation of the engineering trio of Miksa Déri - Ottó Titusz Bláthy - Károly Zipernowszky was the alternating current electrical power distribution system with iron-core transformers, an improvement on the Gaulard & Gibbs system (1885). Its main advantage over Edison's direct current system was its ability to transmit power economically over greater distances.

By the mid-1890s, the Ganz factory had grown to become the largest electrical engineering company in the Austro-Hungarian Empire with domestic roots (i.e. it was not a subsidiary of a company outside the Monarchy), and by the turn of the century alone it had built some 200 power plants outside Hungary, including the Societa Edison power plant in Milan, the power plants in Turin, Grenoble, Livorno, Treviso, Innsbruck, Caransebes and Timisoara. Its most important markets are in the western part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where Ganz, together with the Hungarian Mortgage Bank and the Unionbank of Vienna, founded in 1889 Internationale Elektrizitäts-A.-G. as a financing company to build up its market and Italy, where it established a market presence with a network of engineering offices and the Societa generale per lo Sviluppo delle Imprese elettriche in Italia ("Sviluppo") with a financing company (shareholders in addition to Ganz: Magyar Általános Hitelbank, Creditanstalt, S.M. v. Rothschild, Banca Commerciale of Milan and Gesellschaft für elektrische Unternehmungen ("Gesfürel") of Berlin). Other major markets for Ganz were Russia and South America, but it also exported its electrical engineering products from Western and South-Eastern Europe to Australia.

The 1880s and 90s saw a fierce battle between the different energy transmission systems. Ganz was forced into years of litigation to defend the validity of its patents against AEG and Siemens in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy and Germany. The lengthy litigation was settled, but it proved that Ganz's capital strength and personnel capacity meant that it could only build lasting and significant markets and defend its patents in the Monarchy and Italy.

From 1892 Ganz also manufactured electric vehicles, e.g. mining locomotives, and participated in the electrification of urban railways (1892 Budapest-Újpest-Rákospalotai Electric Railway Ltd, Founders: Ganz, Magyar Ipar und Kereskedelmi Bank, Wiener Bankverein and Jakob Landau Bankhaus Berlin). In 1894-95, the Hungarian General Credit Bank bought up the majority of Ganz's shares.

Ganz also played a part in the development of large-scale railway traction. Kálmán Kandó's three-phase system was tested on the Val Tellina line in Italy. Due to the financial loss caused by the protracted (1898-1902) development and the expected lack of domestic orders, Ganz did not support further developments. Kando and his team were employed by the American company Westinghouse in Italy, where their system electrified a large part of the railways, which Sistema Italiana in the history of technology.

In 1906, Ganz's electrotechnical division became an independent joint-stock company under the name Ganz-éle Villamossági Gyár Rt. with the participation of the German AEG, but the following year - partly due to political pressure - the German owner was bought out by Hitelbank.

By the mid-1890s the Ganz product range has been significantly expanded. In addition to railway wheels, crossings and guide rails, mill rollers, bark-cast artillery shells, architectural and engineering parts, fittings, mainly pipes, the foundry also produced metal and steel castings from the late 1880s. Mechanical engineering included the following product groups: cylinders, cranes, railway switchgears, turntables and shunting gears, Mechwart friction clutches, water turbines for mills, baths, sawmills, post, furniture, paper and iron works, then for driving electrical machinery, pulp and paper mill equipment, and from the 1890s, engines (gas, petroleum, electric). In 1887, Ganz bought the bankrupt Leobersdorf Machinery Works Ltd., which produced, among other things, pulp and paper machinery and war material.and modernised it and set up the production of pulp and paper machinery there. With the wagon factory and the electrical engineering business (design and manufacture of lighting systems and complete power stations, hydro generators from 1897, turbo-generators from 1903), Ganz developed into one of Hungary's most prestigious factories in many branches of foundry, mechanical and electrical engineering.

1911-1929: Ganz and Company Danubius Machine, Waggon and Shipyard Ltd.

In 1911, in preparation for the war, Ganz bought all the shares of Danubius Ship and Machine Works Ltd. (formerly Danubius-Schoenichen-Hartmann, a united ship and machine works Ltd.), which was also owned by the Hungarian General Credit Bank. The merger eliminated the competition between the two factories, e.g. in the production of wagons, and allowed better use of the sites. Danubius was the most important shipbuilding factory in the country, with plants in Budapest (Újpest), Fiume and Portore; since 1906 it had also built warships to the designs of the Stabilimento Tecnico in Trieste. Ganz-Danubius modernised the design and production of warships through Ganz's experience in engine and motor production, British and German patents and manufacturing investments, and thus succeeded in winning the quota orders for Hungary from the Monarchy's naval programme.

This means that in 1912, in Rijeka, the SMS Heligoland fast cruiser and three Tatra-class destroyers in Portore: the SMS Tatras, the SMS Lake Balaton and the SMS Csepel. in 1913 in Fiume, the SMS Novara fast cruiser and three more Tatra-class destroyers in Portoré: the SMS Lika, the SMS Orjen and the SMS Triglav. On 17 January 1914, in Fiume, the pinnacle of Hungarian warship construction at the time, the SMS St Stephen's the battleship and the electric sea-testing submarine built for the Berlin Aquarium, the Loligot.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Ganz was one of the largest companies in the country, with about 10,000 workers, foundries in Budapest and Petrova Gora, machine factories in Budapest, Ratibor and Leobersdorf, a wagon factory in Budapest, shipyards in Budapest, Fiume and Portore, an electrical engineering factory in Budapest, and a well-established brand name abroad.

International cooperation during the First World War

In 1912, Ganz, Weiss Manfréd and the Hungarian General Credit Bank founded the Hungarian Aircraft Factory Ltd. with the participation of the businessman Camillo Castiglioni from Trieste and the Austrian Lohner Works, who played an important role in the creation of the Austrian aircraft industry. Hansa und Brandenburgische Flugzeugwerke became one of the largest manufacturers in the Monarchy after the capital investment and the transfer of its structural drawings, and after the reorganisation of the factory (1916). In 1916, Ganz and Österreichische Fiat Werke founded Ganz-Fiat Magyar repülőgépmotorgyár rt. Thus, during the war, Ganz served the Monarchy's war effort by manufacturing and repairing road and rail transport vehicles (e.g. military trucks under Fiat and later Büssing licences, disinfection and artillery equipment), war and cargo ships, aircraft and aircraft engines, cast iron grenades, ship and aircraft power equipment.

1920s

The loss of the war, the financial damage caused by the Romanian occupation, the break-up of the Monarchy and the significant loss of territory in Hungary triggered a transformation crisis in the Hungarian machinery industry. The production capacity of the machinery industry, which was heavily concentrated in the capital, far exceeded the reduced consumption of the rest of the country, which was financially depleted. Access to export markets became more difficult, as the ubiquitous expansion of machinery production during the war led to increased competition, depressed prices and the imposition of new trade barriers.

After the First World War, Ganz's shipyard in Fiume was transformed into a separate joint stock company (Cantieri Navali del Quarnaro Societa Anonima Fiume) with the participation of Banca Italiana di Sconto and Societa Alti Torni Fonderie ed Acciaieni di Terni Anonima, while the Portore plant continued to operate as a Yugoslavian independent company (Jugoslavenska Brodogradilista d.d. Portore).

One of the most important consequences of the country's lack of capital for Ganz was that the Kando second main line electrification system was finally tested in operation with a British government loan, through the joint efforts of British and Hungarian companies. This involved the electrification of the Budapest-Hegyeshalom line and the construction of the Tatabánya power station between 1928 and 1932, the latter supplying three counties in addition to the needs of the railway. Despite the demonstration of the viability of the Kandó system, however, railway electrification in Hungary was halted for decades.

Another important consequence of the lack of capital was the slowdown in the development of the electrical engineering business, which was then operating as a separate company. Between the two world wars, the increasing size of the electrification projects required significant product development (e.g. turbine capacity) and financial backing (investment loans for product development and potential customers), which the company could not keep up with due to the decline in the equity of Ganz's own capital and the financial situation of the Hungarian and potential Austrian banks. Ganz's competitive position was characterised by the fact that it was not a member of the cartel uniting the world's leading manufacturers of electrical machinery (International Electric Association, 1930, members: International General Electric, International Westinghouse Electric Corp., four British manufacturers, AEG, Siemens and the Swiss Brown-Boveri & Cie.), but in 1934 it was able to join the cartel of the largest European electricity meter manufacturers (Accord de Paris, 1933), which had been formed the previous year.

The traditional products shipped to the neighbouring countries as reparations postponed the need to renew the Ganz-Danubius product range for a few years. However, low levels of public investment in infrastructure and declining export shipments and profits led to the company's indebtedness. In the second half of the 1920s, Ganz-Danubius merged four smaller machine factories to reduce competition (Schlick-Nicholson Gépgyár rt., Gép- und Vasútfelszerelési Rt., Erste Magyar Nährógép- und Kerékpárgyár rt., Dr. Lipták & Társa építési és Társa vasipari rt.), and in 1929 Ganz Electricity Rt. merged with the parent company.

1929-1946: Ganz & Co. Danubius Electricity, Machine, Waggon and Shipyard Ltd.

In addition to mergers, the company's management also sought other ways out of the transformation crisis and later the global economic crisis. First, Ganz was a leading or significant member of major cartels in the industry. One of the declared aims of these was to help members adapt to the market conditions created by the new national borders. They were of practical use mainly in helping to weather the Great Depression by preventing to some extent a sharp fall in prices and, to a lesser extent, by facilitating product specialisation between members.

On the other hand, the company attracted fresh capital: in 1930, General Electric and the German AEG, within a few years AEG alone became the owner of 25% of Ganz's shares. Under agreements with foreign owners, Ganz's electrical plant was allowed to use their patents with territorial restrictions, and the export of the electrical plant was restricted and the export of mechanical machinery such as diesel engines to South America was subsidised.

In the long term, the most significant element of crisis management has been product development. The excellent diesel engines designed by György Jendrassik were mass-produced by Ganz from the late 1920s. In the 1930s, in addition to the electrification of the railways, the use of diesel locomotives or motor coaches, which required less investment, was another way of replacing steam traction. Motor coaches with Jendrassik engines were suitable for cost-effective supply to the rural areas of the new Hungary. MÁV supported product development by ordering several different types. Ganz motor coaches performed well in suburban traffic in Western Europe and in the mountainous areas of Yugoslavia. Using this experience, Ganz played a leading role in the motorisation of railways in Argentina before the outbreak of the World War, and planned to enter the markets of less industrially developed, large countries (South America, Africa (e.g. Egypt, Rhodesia)).

Hungarian Railcar Test Drive (1938) Source: NFI Film Archive

In order to boost trade with Egypt and the Middle East, Ganz designed a low-draft, high-stability Danube cruiser with Jendrassik engines, but only six were built by 1941.

The launching of the "Szeged" (1936) Source: NFI Film Archive

It was mainly the export success of diesel engines and motor cars, investments in transport and electricity in the second half of the 1930s, followed by investments in the country in the run-up to war, and the halving of the share price in 1938, that enabled Ganz to stabilise its financial situation, which had deteriorated further in the late 1930s due to the shocks of the Great Depression.

Second World War

During the Second World War, the Ganz Wagon and Machine Works was more involved in military production. The Ganz Electricity Factory carried out repairs and extensions to various industrial plants and power stations providing public lighting, supplied electric locomotives, electric motor cars, large transformers, electrical equipment for transport companies; its largest work was the manufacture of equipment for the new Matravaidek Power Station.

During the war, Ganz's capital was increased several times, and the shares were taken over by the Hitelbank in exchange for the company's debts. Since AEG did not buy any of the new shares, its share in Ganz's capital steadily decreased. In 1943, Hitelbank bought back AEG's shares in Ganz, and the company was again fully Hungarian-owned.

1945-1989

During the war, Ganz suffered extensive damage, with the electricity factory being the worst affected.

In 1946, to support the reconstruction of the country, the Hungarian government nationalised the mines, electricity distribution companies and five strategic enterprises, including Ganz, and placed them under the unified control of the newly organised Heavy Industry Centre. In 1949, the Ganz factory was split into independent state-owned companies (Ganz Wagon and Machine Works, Ganz Electricity Works, Ganz Shipyard, Ganz Switch and Appliance Works, Ganz Power Meter Works). In 1959, Ganz Wagon and Machine Works was merged with MÁVAG, which operated under the name GANZ-MÁVAG Locomotive, Wagon and Machine Works until the end of 1988.

After the regime change

Several smaller companies were established on the ruins of the bankrupt Ganz-MÁVAG (Ganz Gépgyár Vállalat, Ganz Motor Kft., Ganz Energetikai Gépgyártó Kft.) Ganz's mechanical engineering activities were continued by Ganz Motor Kft., Ganz Vasúti Forgóváz- és Járműgyártó Kft., Ganz Motor Kft., Ganz Vasúti Forgóváz- és Járműgyártó Kft., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt., Ganz Holding Zrt, Ganzeg Kft. and Ganz Hydro Kft., with the following products: railway vehicles, components and parts, railway transmission equipment, diesel and gas engines, generating sets, machinery and steel structures, automatic irrigation equipment, water supply systems. The Ganz Electricity Factory tradition is continued by Ganz Transformer and Electrical Rotating Machinery Manufacturing Ltd., which manufactures transformers and related steel structures, motors and generators.

A large-scale landscaping programme started in 2001 at the former Ganz factory in Buda. The Millenáris Park, which preserves parts of the former industrial monuments, was completed in its current form in 2022.

Sources

Berlász, Jenő, The first half century of the Ganz factory 1845-1895, in Tanulmányok Budapest múltjából (1957) 12, pp. 349-458.

Boross, Elizabeth A., Inflation and industry in Hungary 1918-1929. Haude & Spener, Berlin, 1994.

Hidvégi, Mária, Connecting to the world market. Hungary's leading electrical engineering companies 186-1949. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2016.

Hidvégi, Mária, The Ganz-Jendrassik diesel cars in Argentina, in AETAS 29 (2014) 4, pp. 45-64.

Hidvégi, Mária, Crises and Responses: government policies and the Machine-building Cartels in Hungary, 1919-1949, Enterprise and Society 20 (March 2019) 1, 89-131.

Pogány, Ágnes, Bankers and business partners. The Hungarian General Credit Bank and its corporate clients between the two world wars, in. 55-66.

Rév, Pál, The circumstances of the development of the Hungarian aircraft industry, in Czére Béla (ed.), Yearbook of the Museum of Transport 2. 1972-1973. Közlekedési Dokumentációs Vállalat, Budapest, 1974, pp. 221-233.

István Szécsey, Ganz railway vehicles from 1920 to 1959. Budapest, Indóház Kiadó, 2013.

Szekeres, József, The History of Shipbuilding in Újpest I (1863-1911) and II (1912-1944), in Studies on the Past of Budapest (1961) 14, pp. History of History of Budapest, History of History in Historical Perspectives (1961), pp. 483-531 and (1963) 15, pp. 637-693.

Szekeres, József; Árpád Tóth, The History of the Klement Gottwald (Ganz) Electricity Factory. Közgazdasági és Jogi Kiadó, Budapest, 1962.

The different volumes of the Great Hungarian Compass (formerly Mihók's)

Intenet sources:

Resch, Andreas, The beginning of aircraft construction in Austria.

https://www.ganz-holding.hu/ceginformacio

https://www.ganzelectric.com/rolunk/

https://www.gtkb.hu/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14&Itemid=255&lang=hu