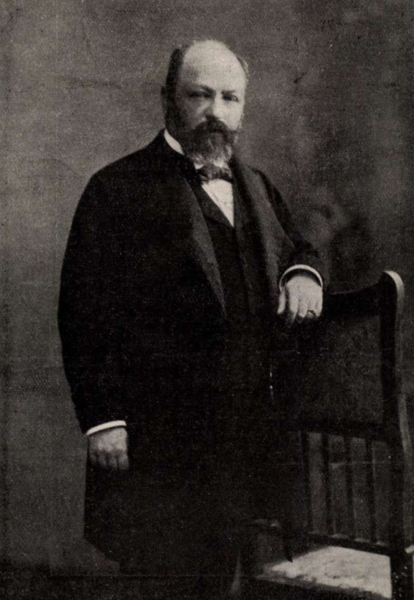

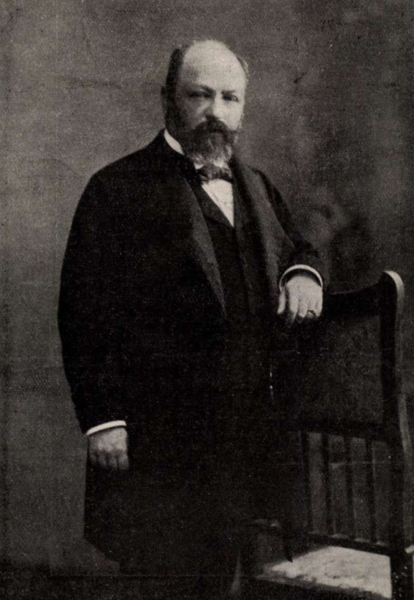

Henrik Jellinek from Haraszti

Henrik Jellinek is as much a forgotten figure in the history of Budapest as his career colleague and business rival Mór Balázs. Without Jellinek, the capital's public transport system, which made Budapest's development into a metropolis possible, might not have been built. The fact that he is not today considered one of the greatest Budapest developers is also due to his sudden and perhaps inglorious departure from the BKVT, and to the fact that the post-1945 city administration tried to discredit the capitalist business leaders.

At the time of Jellinek's death in the Metropolitan Assembly, Vilmos Sümegi MEP said.which he created for Jelli in Budapest, blessed be his name. I can honestly say that I resent the fact that, apart from Tivadar Bódy and István Milotay, there were no other members of the legislative committee, the city was not represented, and we did not even place a wreath on Jellinek's Henrik's grave, although he really deserved it. He was the first to say that the working-class districts should be provided with good and cheap transport and that where this is hindered by the high-speed railways, elevated railways and viaducts should be built."

In 1971 Mihály Tóth wrote an article about him in the journal Budapest entitled: "The great Jellinek. The rise and fall of a panamanian."

He came from a prominent Israelite family, one of his uncles Adolf Jellinek served as Chief Rabbi of Vienna, and the philosopher Herman Jellinek was shot by Windisgrätz during the Vienna Revolution. His father, Mór Jellinek, moved to Pest in the early 1850s, where he began trading in grain. He also did not reject new business opportunities, and became one of the founders of the Pesti Közúti Vasút Társaság (Pest Road Railway Company) with Sándor Károlyi and Ernő Hollán. The business was successful, much more successful than the Buda Road Railway Company on the other side of the Danube. As part of the expansion of PKVT, the opportunity to link the two parts of the city via the Margaret Bridge, the company bought BKVT, and the resulting Budapest Public Railway Company (also known as BKVT) had a network of horse-drawn railways covering the whole of the capital. At this time, his son Henrik Mór was also working for the company. Henrik Jellinek was born in 1853 in Pest, and after graduating from the Commercial Academy, he joined BKVT in 1869. He took over the management of the company in 1883, after his father's death. This decade, the 1880s, was the golden age of the horse-drawn railway.

The horse railway company's lines were increasingly covering Budapest, but the BKVT was already working on a plan to connect the settlements around Budapest to the capital's horse railway network with local railways of local interest. The construction of these local interest railways was made possible by Act XXX of 1880, which allowed them to be built as branch lines with a simpler structure than main line railways, i.e. much cheaper to build than conventional main line railways. The BKVT saw an opportunity in the fact that even then, more and more people were moving out of the city, mostly along the railway lines, and the company saw a significant business opportunity in these commuters from the Budapest area.

Based on foreign examples - Jellinek's experience abroad also contributed to this - the steam-powered Budapest-Soroksár-Haraszti, Budapest-Szentendre and Kerepes-Cinkota HÉV lines were built on the initiative of BKVT, at Jellinek's suggestion. In one and a half years, between 1887 and 1889, the local rail connections in Budapest were developed into a 53-kilometre network. To operate the HÉVs, BKVT set up a subsidiary, Budapest Local Interest Railways Ltd, headed by Henrik Jellinek, as was the parent company.

The BKVT had a virtual monopoly on the capital's horse railway network, but this was threatened by the tramway initiated by Mór Balázs. Jellinek very quickly realised that this was the future, and BKVT reacted quickly, starting electrification itself. The electrification seriously affected the horse railway company's concession, and in 1895, in a two-day council debate, the company succeeded in obtaining a concession for the electrified network for another 48 years. The BKVT therefore electrified practically the entire former horse-railway network in Budapest within a year and a half.

Jellinek has not only been busy developing the network and seizing new business opportunities, but also developing new business policies. He introduced the tobacconist's ticket, a kind of 10-piece collective ticket that could be bought in tobacconists' shops, making a ticket cheaper than if you bought it in the vehicle. He initiated the reform of the BKVT tariff, a kind of zone tariff was introduced, the small section tickets, which meant a significant reduction in fares, but this led to a surge in traffic, 11.3 million passengers in 1886, when the tariff was introduced, and by 1896 this number had increased to 26.4 million.

Henrik Jellinek was a bachelor, never married, and according to an obituary, a strangely reserved man who reserved all his affection for his company. In the Magyar Hírlap of 11 November 1933, Mihály Pásztor wrote about him:

"Jellinek was not a popular man, he was considered too cold. He lacked sentimentality and was more of a businessman than a popular man. His unpopularity was slowly rubbing off on the railways he managed. For fifty years, the people of Budapest had been scolding the public railways, and all this scolding had almost made this public transport enterprise, which sometimes provoked criticism, popular."

Despite the fact that he was not a popular man, the people of Budapest attributed all the problems of the horse-drawn tram and later the tram to him. It is true that the government and official circles recognised his work, first as a court councillor and then, after the construction of the tram network, he was given the nobility of the Haraszti in recognition of the importance of this work.

Jellinek was actively involved in social life, chairman of the Chamber of Commerce and the Budapest District Sickness Fund. He also played a role in the explanation of economic terms. In addition to running the BKVVT - and BHÉV - he was a member of the board of directors of the Hungarian Commercial Bank of Pest, which held the majority of the shares in both companies, from 1901.

With the advent of the tramway, BKVT's monopoly was broken, with the Budapest Public Railway Company, which operated brown coaches, and the Budapest Municipal Electric Railway, which operated yellow coaches, coexisting side by side. (The two companies were able to work together on the underground, which they operated jointly.) Contemporaries saw the BKVT as a better deal, according to a recollection in the 5 November 1933 issue of the Magyar Hírlap, "One day someone asked Zsigmond Kornfeld, the famous CEO of the Hitelbank, for advice on what paper to invest his fortune in.

After 42 years at the BKVT, he was dismissed in 1911. At that time, the shareholder structure changed, and the entrepreneur Simon Krausz bought a large number of shares, which meant that his interest became the majority. Jellinek, who, according to press reports at the time, was to leave with a severance payment of 300 000 kronor and a pension, was simply dismissed. However, this was prevented by the new CEO, Pál Sándor, as an audit of the company's accounts revealed that Jellinek had previously entered into agreements whereby he was entitled to a 5% share of all company investments, which over the years had meant an income of SEK 2 250 000 for the CEO. According to the protocol and agreement of 5 December 1911 (quoted by Mihály Tóth), "

"The parties, not wishing to submit the dispute to a judicial decision, agreed after lengthy negotiations that Mr Henrik Jellinek would waive his contractual severance pay and pension and reimburse the Budapest Local Interest Railways Joint Stock Company 625 000 crowns from the commissions received."

Jellinek resigned from his severance pay and pension and retired from the BKVT, living alone in his palace at 18 Lipót körút. After leaving the BKVT, however, he continued to write numerous articles on economics. He had also been involved in writing before, publishing a study entitled 'On working holidays' as early as 1890. After leaving the BKVT, he often published under the pseudonym Cenzor, including 'Magyar Eisenbahn Politika' (Hungarian Railway Politics). After World War I, he became a financial contributor to the daily newspaper Uj Nemzedék.

He did not take on any new economic tasks, but he hoped that after the takeover of BKVT by the capital, as the most important figure in the sector, he would be asked to become an expert, but this did not happen.

Henrik Jellinek finally died after a long illness in 1927, his heirs were his three brothers (Arthur, Marcel and Lajos) and their descendants, because Henrik Jellniek was a lonely man who never married. This is why it caused such a stir when, years after his death in 1930, Luiza Blaim, a nurse who had cared for him in the last years of his life, brought a lawsuit against his heirs, claiming that she had had tender feelings for the wealthy, ailing old man, who was in his 70s at the time. Although Lujza Blaim received 30 million kroner after Jellinek's death (which was not a very large sum because of inflation), the nurse claimed that Jellinek had promised her much more, and that he was asking for a lump sum of 50,000 pence and a monthly pension of 300 pence.

Sources

- Mihály Tóth:The Glory and Fall of the Great Jellinek A panamista, Budapest, 1971/9

- Gábor Zsigmond: I apologize, It happened by chance, Budapest, 2014/12 issue

- The horse-drawn railway and the rubber-wheeled tram, Magyar Hírlap 1933 November 5

- Who was angry with the whole of Budapest, Magyar Hírlap 12 April 1927

Born: 22 December 1853.

Place of birth: Budapest

Date of death: 11 April 1927.

Place of death: Budapest

Occupation:Managing Director, Publisher

Parents: Mór Jellinek

Spouses:

Children:

Author: by Domonkos Csaba

Born: 22 December 1853.

Place of birth: Budapest

Date of death: 11 April 1927.

Place of death: Budapest

Occupation:Managing Director, Publisher

Parents: Mór Jellinek

Spouses:

Children:

Author: by Domonkos Csaba

Henrik Jellinek from Haraszti

Henrik Jellinek is as much a forgotten figure in the history of Budapest as his career colleague and business rival Mór Balázs. Without Jellinek, the capital's public transport system, which made Budapest's development into a metropolis possible, might not have been built. The fact that he is not today considered one of the greatest Budapest developers is also due to his sudden and perhaps inglorious departure from the BKVT, and to the fact that the post-1945 city administration tried to discredit the capitalist business leaders.

At the time of Jellinek's death in the Metropolitan Assembly, Vilmos Sümegi MEP said.which he created for Jelli in Budapest, blessed be his name. I can honestly say that I resent the fact that, apart from Tivadar Bódy and István Milotay, there were no other members of the legislative committee, the city was not represented, and we did not even place a wreath on Jellinek's Henrik's grave, although he really deserved it. He was the first to say that the working-class districts should be provided with good and cheap transport and that where this is hindered by the high-speed railways, elevated railways and viaducts should be built."

In 1971 Mihály Tóth wrote an article about him in the journal Budapest entitled: "The great Jellinek. The rise and fall of a panamanian."

He came from a prominent Israelite family, one of his uncles Adolf Jellinek served as Chief Rabbi of Vienna, and the philosopher Herman Jellinek was shot by Windisgrätz during the Vienna Revolution. His father, Mór Jellinek, moved to Pest in the early 1850s, where he began trading in grain. He also did not reject new business opportunities, and became one of the founders of the Pesti Közúti Vasút Társaság (Pest Road Railway Company) with Sándor Károlyi and Ernő Hollán. The business was successful, much more successful than the Buda Road Railway Company on the other side of the Danube. As part of the expansion of PKVT, the opportunity to link the two parts of the city via the Margaret Bridge, the company bought BKVT, and the resulting Budapest Public Railway Company (also known as BKVT) had a network of horse-drawn railways covering the whole of the capital. At this time, his son Henrik Mór was also working for the company. Henrik Jellinek was born in 1853 in Pest, and after graduating from the Commercial Academy, he joined BKVT in 1869. He took over the management of the company in 1883, after his father's death. This decade, the 1880s, was the golden age of the horse-drawn railway.

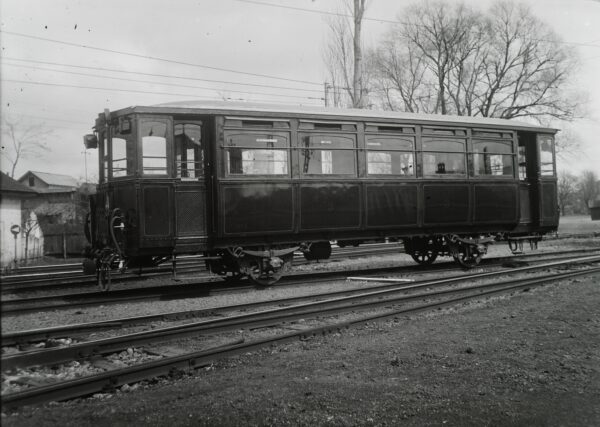

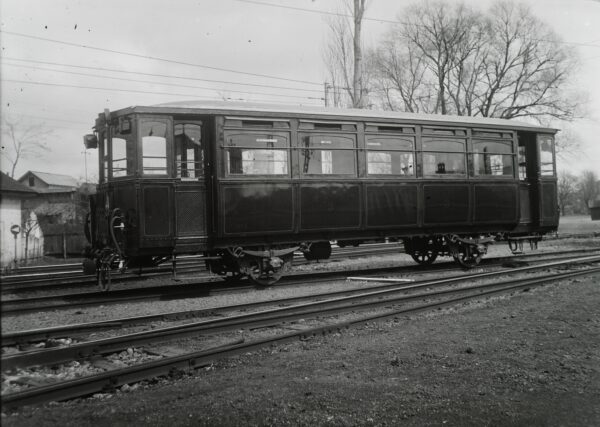

The horse railway company's lines were increasingly covering Budapest, but the BKVT was already working on a plan to connect the settlements around Budapest to the capital's horse railway network with local railways of local interest. The construction of these local interest railways was made possible by Act XXX of 1880, which allowed them to be built as branch lines with a simpler structure than main line railways, i.e. much cheaper to build than conventional main line railways. The BKVT saw an opportunity in the fact that even then, more and more people were moving out of the city, mostly along the railway lines, and the company saw a significant business opportunity in these commuters from the Budapest area.

Based on foreign examples - Jellinek's experience abroad also contributed to this - the steam-powered Budapest-Soroksár-Haraszti, Budapest-Szentendre and Kerepes-Cinkota HÉV lines were built on the initiative of BKVT, at Jellinek's suggestion. In one and a half years, between 1887 and 1889, the local rail connections in Budapest were developed into a 53-kilometre network. To operate the HÉVs, BKVT set up a subsidiary, Budapest Local Interest Railways Ltd, headed by Henrik Jellinek, as was the parent company.

The BKVT had a virtual monopoly on the capital's horse railway network, but this was threatened by the tramway initiated by Mór Balázs. Jellinek very quickly realised that this was the future, and BKVT reacted quickly, starting electrification itself. The electrification seriously affected the horse railway company's concession, and in 1895, in a two-day council debate, the company succeeded in obtaining a concession for the electrified network for another 48 years. The BKVT therefore electrified practically the entire former horse-railway network in Budapest within a year and a half.

Jellinek has not only been busy developing the network and seizing new business opportunities, but also developing new business policies. He introduced the tobacconist's ticket, a kind of 10-piece collective ticket that could be bought in tobacconists' shops, making a ticket cheaper than if you bought it in the vehicle. He initiated the reform of the BKVT tariff, a kind of zone tariff was introduced, the small section tickets, which meant a significant reduction in fares, but this led to a surge in traffic, 11.3 million passengers in 1886, when the tariff was introduced, and by 1896 this number had increased to 26.4 million.

Henrik Jellinek was a bachelor, never married, and according to an obituary, a strangely reserved man who reserved all his affection for his company. In the Magyar Hírlap of 11 November 1933, Mihály Pásztor wrote about him:

"Jellinek was not a popular man, he was considered too cold. He lacked sentimentality and was more of a businessman than a popular man. His unpopularity was slowly rubbing off on the railways he managed. For fifty years, the people of Budapest had been scolding the public railways, and all this scolding had almost made this public transport enterprise, which sometimes provoked criticism, popular."

Despite the fact that he was not a popular man, the people of Budapest attributed all the problems of the horse-drawn tram and later the tram to him. It is true that the government and official circles recognised his work, first as a court councillor and then, after the construction of the tram network, he was given the nobility of the Haraszti in recognition of the importance of this work.

Jellinek was actively involved in social life, chairman of the Chamber of Commerce and the Budapest District Sickness Fund. He also played a role in the explanation of economic terms. In addition to running the BKVVT - and BHÉV - he was a member of the board of directors of the Hungarian Commercial Bank of Pest, which held the majority of the shares in both companies, from 1901.

With the advent of the tramway, BKVT's monopoly was broken, with the Budapest Public Railway Company, which operated brown coaches, and the Budapest Municipal Electric Railway, which operated yellow coaches, coexisting side by side. (The two companies were able to work together on the underground, which they operated jointly.) Contemporaries saw the BKVT as a better deal, according to a recollection in the 5 November 1933 issue of the Magyar Hírlap, "One day someone asked Zsigmond Kornfeld, the famous CEO of the Hitelbank, for advice on what paper to invest his fortune in.

After 42 years at the BKVT, he was dismissed in 1911. At that time, the shareholder structure changed, and the entrepreneur Simon Krausz bought a large number of shares, which meant that his interest became the majority. Jellinek, who, according to press reports at the time, was to leave with a severance payment of 300 000 kronor and a pension, was simply dismissed. However, this was prevented by the new CEO, Pál Sándor, as an audit of the company's accounts revealed that Jellinek had previously entered into agreements whereby he was entitled to a 5% share of all company investments, which over the years had meant an income of SEK 2 250 000 for the CEO. According to the protocol and agreement of 5 December 1911 (quoted by Mihály Tóth), "

"The parties, not wishing to submit the dispute to a judicial decision, agreed after lengthy negotiations that Mr Henrik Jellinek would waive his contractual severance pay and pension and reimburse the Budapest Local Interest Railways Joint Stock Company 625 000 crowns from the commissions received."

Jellinek resigned from his severance pay and pension and retired from the BKVT, living alone in his palace at 18 Lipót körút. After leaving the BKVT, however, he continued to write numerous articles on economics. He had also been involved in writing before, publishing a study entitled 'On working holidays' as early as 1890. After leaving the BKVT, he often published under the pseudonym Cenzor, including 'Magyar Eisenbahn Politika' (Hungarian Railway Politics). After World War I, he became a financial contributor to the daily newspaper Uj Nemzedék.

He did not take on any new economic tasks, but he hoped that after the takeover of BKVT by the capital, as the most important figure in the sector, he would be asked to become an expert, but this did not happen.

Henrik Jellinek finally died after a long illness in 1927, his heirs were his three brothers (Arthur, Marcel and Lajos) and their descendants, because Henrik Jellniek was a lonely man who never married. This is why it caused such a stir when, years after his death in 1930, Luiza Blaim, a nurse who had cared for him in the last years of his life, brought a lawsuit against his heirs, claiming that she had had tender feelings for the wealthy, ailing old man, who was in his 70s at the time. Although Lujza Blaim received 30 million kroner after Jellinek's death (which was not a very large sum because of inflation), the nurse claimed that Jellinek had promised her much more, and that he was asking for a lump sum of 50,000 pence and a monthly pension of 300 pence.

Sources

- Mihály Tóth:The Glory and Fall of the Great Jellinek A panamista, Budapest, 1971/9

- Gábor Zsigmond: I apologize, It happened by chance, Budapest, 2014/12 issue

- The horse-drawn railway and the rubber-wheeled tram, Magyar Hírlap 1933 November 5

- Who was angry with the whole of Budapest, Magyar Hírlap 12 April 1927